Modern Rodding TECH

InTheGarageMedia.com

This Eric Black rendering of Cody Walls’ East Coast–style Deuce coupe details the deeply channeled proportions achievable while maintaining driveability and a modicum of comfort.

Lowering the Profile on a ’32 Ford

Photography by Cody Walls

Photography by Cody Wallsn the earliest days of our hobby, innovative hot rodders identified that increasing power wasn’t the only way to go faster in their stripped-down coupes and roadsters. Decreasing wind resistance was also key. Chopped tops and lowered stances not only looked cool, they reduced the overall height of the bricks-on-wheels these racers were trying to push across the dry lakes. But there was another modification that came into favor early on known as channeling.

The premise is simple: cut out and raise the floor of the car to slide the body down over the frame. The result thins the car’s profile and reduces wind resistance, shaving valuable seconds from e.t.’s in the process. Aesthetically, channeling has just as much impact as chopping a car. Though we all love the styling of American iron from the teens, 1920s, and ’30s, the basis of the designs wasn’t all that far off from the buggies that preceded them—straight-railed, ladder-style frames with steel and wood boxes bolted on top. Stripping the fenders and dropping the body down over the ’rails created a more slippery appearance, hinting at the European sports cars of the era and foreshadowing the design evolution that began in the ’30s when OEs started lowering bodies over frames and continued through the ’60s with the popularization of unibody construction where the body, floor, and frame became one.

While plenty of West Coast hot rods sported channeled bodies, the practice of channeling a car and leaving the top unchopped became a hallmark of East Coast rodding style in the ’50s. Cody Walls is an East Coast fabricator who has always loved the look. He even made his first big splash as a professional builder with his own channeled hot rod, though his choice of raw material—a ’59 Chevy Brookwood wagon—was far more complicated to channel than an early Ford coupe. “I always liked the connection between unchopped, channeled hot rods and the East Coast,” he says. “And I like my stuff low, so channeling was just another way to get things as low as they can be.”

That wagon was eventually sold to finance the launch of his shop, Traditional Metalcraft. In the years that followed as he built his business, he kept thinking about how he would build his ideal of a traditional, East Coast, unchopped and channeled early Ford. “Even when I was building the wagon I had this idea for a ’32 Ford coupe,” he says. “I’d seen a photo of a car on the H.A.M.B.—a Hemi-powered, channeled three-window built in Kansas in the ’50s. It was called ‘Toughy,’ and as soon as I saw it I knew I wanted to build my version of that car but with a Wayne 12-port. So, I was collecting parts for it all those years.”

The interest in channeled cars and in inline engines was sparked at the East Coast Hot Rod Garage, where Walls first worked after graduating from WyoTech. The former came into play when he was tasked with channeling a ’63 Riviera over an Art Morrison Enterprises chassis—which, like the wagon that came later, was a task far more involved than channeling a ’32 Ford. The latter is a result of Walls’ tendency toward the road less traveled.

“I like inlines because of the underdog thing,” he says. “The guys at the Hot Rod Garage taught me about Wayne 12-ports and their racing history—that you could make power with stuff other than a V-8—and it all just appealed to me.”

As he built his wagon, he continued assembling odds and ends for the one-of-these-days ’32. The Wayne 12-port turned up on eBay after an eight-year hunt. Then it took another five before he found a suitable body.

“I’d been looking for an original three-window body with a stock-height roof for several years,” he says, “but nothing ever panned out. Then a couple years ago Kevan Sledge posted one on Instagram and it was everything I was looking for at a price that I could kind of afford.” Sledge is a talented customizer who’s perhaps most well known for the parade of chopped ’39-40 Mercurys that have rolled out of his Northern California shop in the past decade or so. The coupe he was advertising belonged to a customer who had pulled it out of a barn in Sacramento, started to build it, then lost interest.

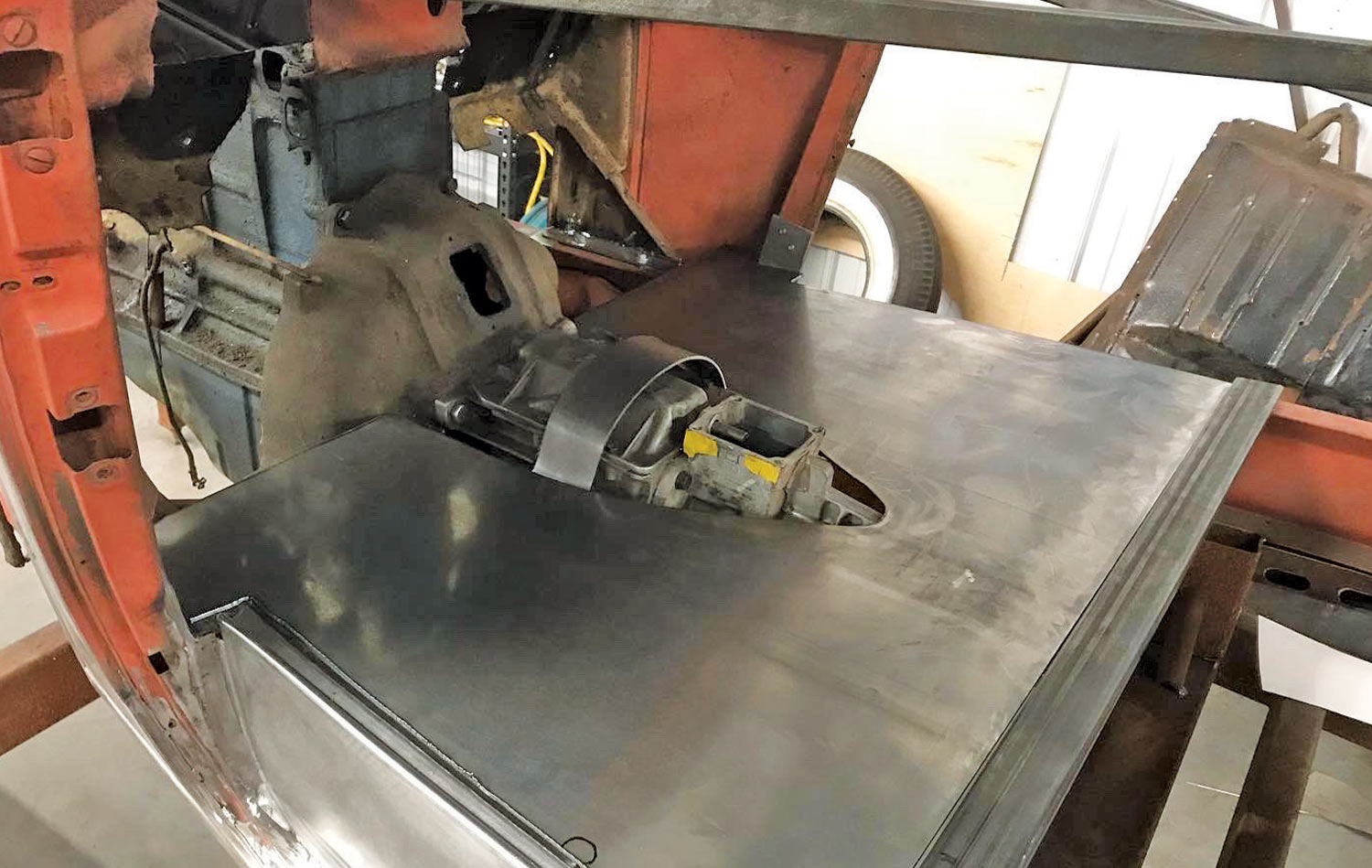

“It was an old hot rod,” Walls says. “But we really don’t know much about its history.” It had been channeled at one time but the floor was now gone. The tail panel bore the signs of having had Pontiac taillights (or something similar) installed, and the rear fenders were bobbed and welded to the quarters, then loaded with lead. But it came with a set of gennie ’rails, both doors and a decklid, and even a loose section of floor from another coupe. Most importantly, it was un-chopped.

As with all his projects, this one is based off a detailed rendering Walls commissioned from Eric Black of e. Black Design Co. Before the first sparks flew, the two were able to work out all the details, from the proper wheelbase (107 inches) to keep the long 261 Chevy from looking out of proportion, to the perfect channel to make the car look cool while still leaving room for 6-foot-tall Walls.

“Channeled cars can be tricky because you’re losing a good bit of space in the cabin,” he says. “[Black] took my height and the length of my legs into account, and since he draws everything to scale, we were able to figure out how deeply we could channel the body and still make it so that I can enjoy it. Because I drive my cars—a lot.”

When all was said and done, Walls channeled the body 9 inches at the firewall and 8 inches at the tail. The resulting rake has a ton of attitude, but thanks to a host of other strategic cuts and tweaks, Walls was able to maintain a comfortable amount of space within the cockpit. For example, sectioning the firewall and saving the factory kick-out at the bottom gained about 3 inches of legroom. Also, he used the trunk floor from a ’32 coupe as a seat pan. Recesses designed to be footwells for rumble seat passengers made convenient nooks for extra seat padding in Walls’ coupe, making for a more comfortable ride without raising the driver’s profile.

In the end, channeling is a game of making incremental gains to maintain as much room as possible, creating space wherever you can find it. Done right, the results are low down and cool, while remaining fully functional—and even comfortable—for the long haul.

VOLUME 3 • ISSUE 25 • 2022