Modern Rodding TECH

InTheGarageMedia.com

Photography by Rodger Lee

Photography by Rodger Lee  Artwork By E. Black Design

Artwork By E. Black Designn any automotive project the chassis is the foundation that holds all the components together. Sometimes a stock chassis can be used, but when the suspension and drivetrain are updated, the chassis usually needs to be strengthened and reconfigured.

This is the first in a series of articles about Greg Heinrich’s outstanding ’35 Chevrolet coupe being built by Ironworks Speed & Kustom, in Bakersfield, California. This is a multi-year, no-holds-barred project and we think you’ll enjoy seeing the bleeding-edge design and fabrication lavished on every component.

The body modifications on this project are subtle, and Eric Black, of e. Black Design Co. was called in at an early stage to make renderings, which was key to keeping all the modifications harmonious and on track. The top has a sweet chop, with the A-pillar laid back, the rear of the body is lengthened around 2 inches, the rear wheelwells are raised, and the body has a wedge section–lowering the front of the grille shell a tasty amount. The fenders are re-contoured for the larger wheels and tires, and there are dozens of unique features you’ll see in future articles, making use of the latest technology available.

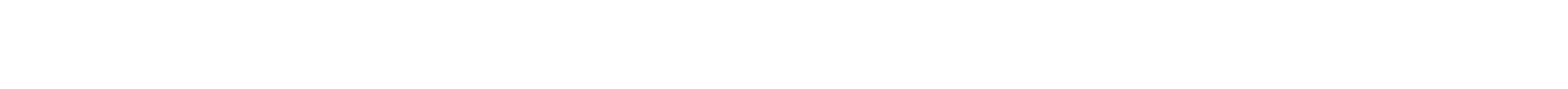

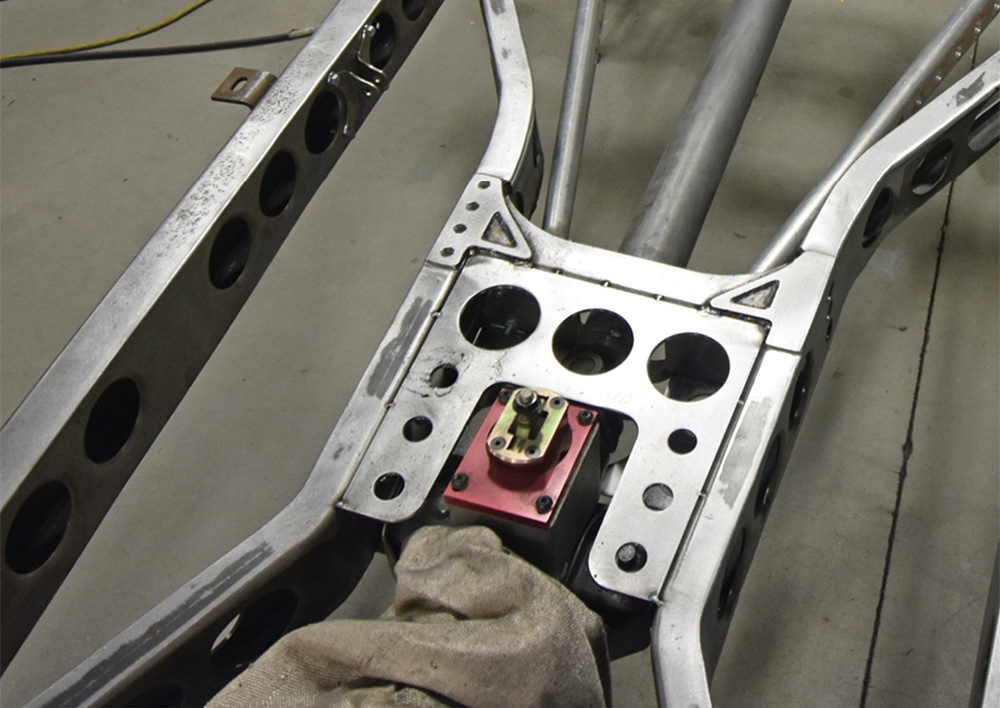

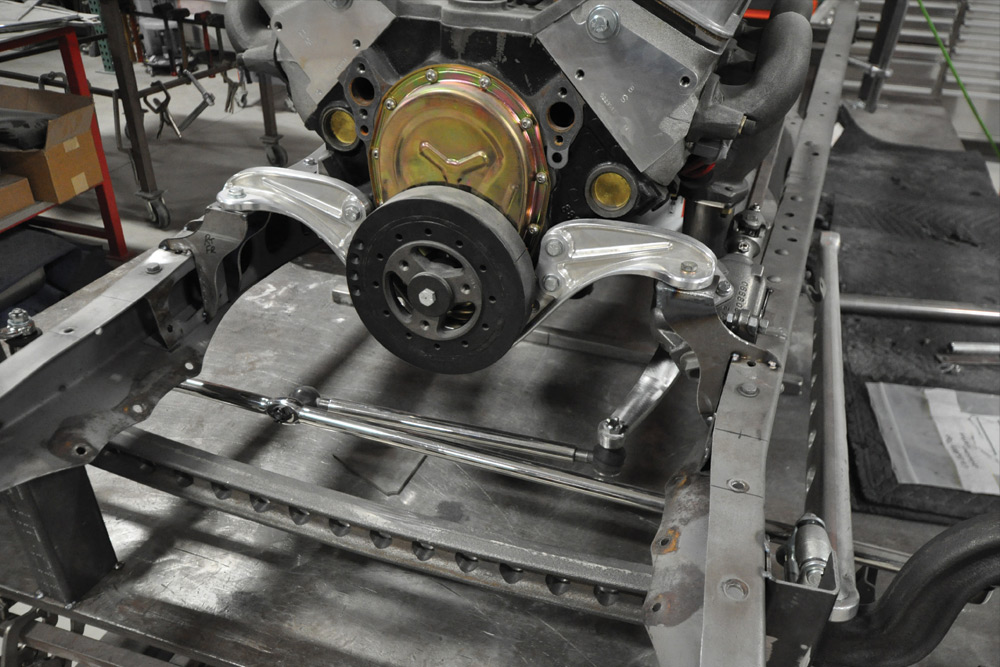

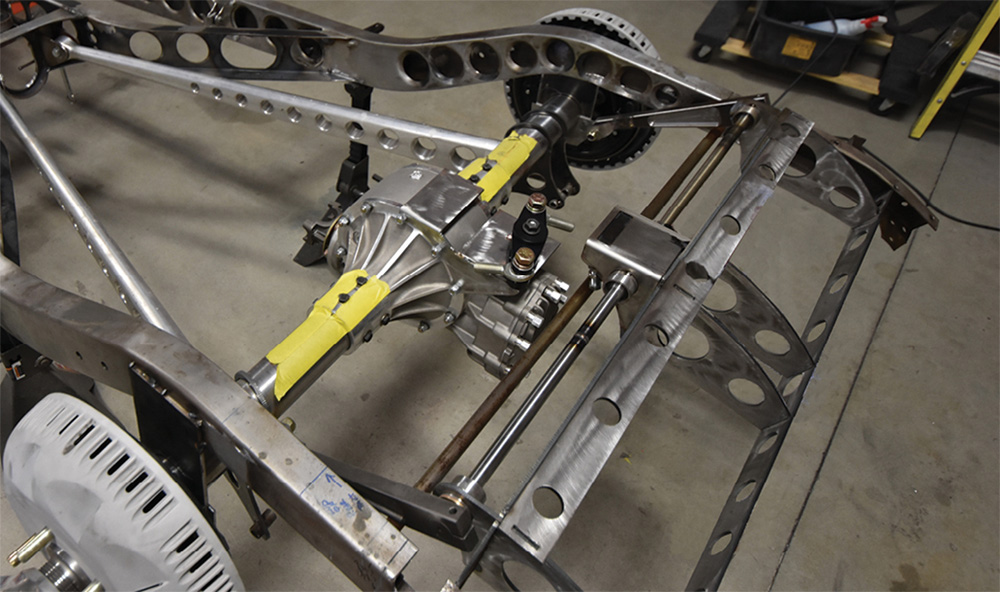

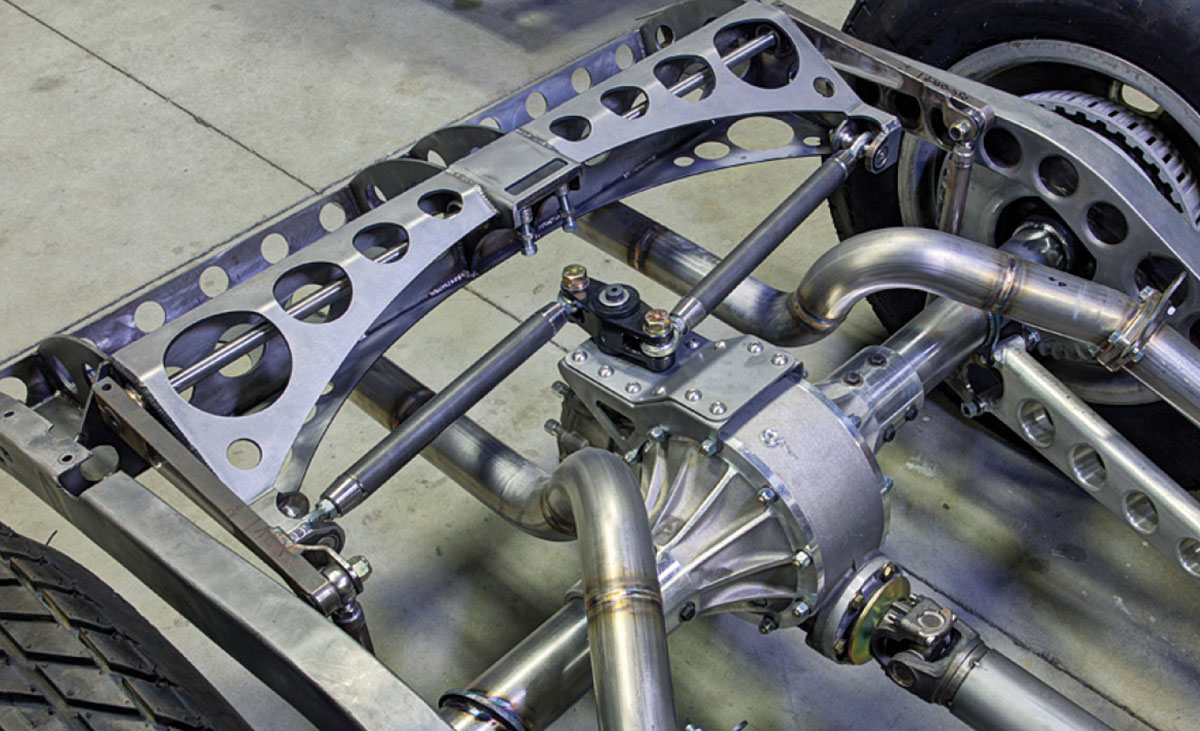

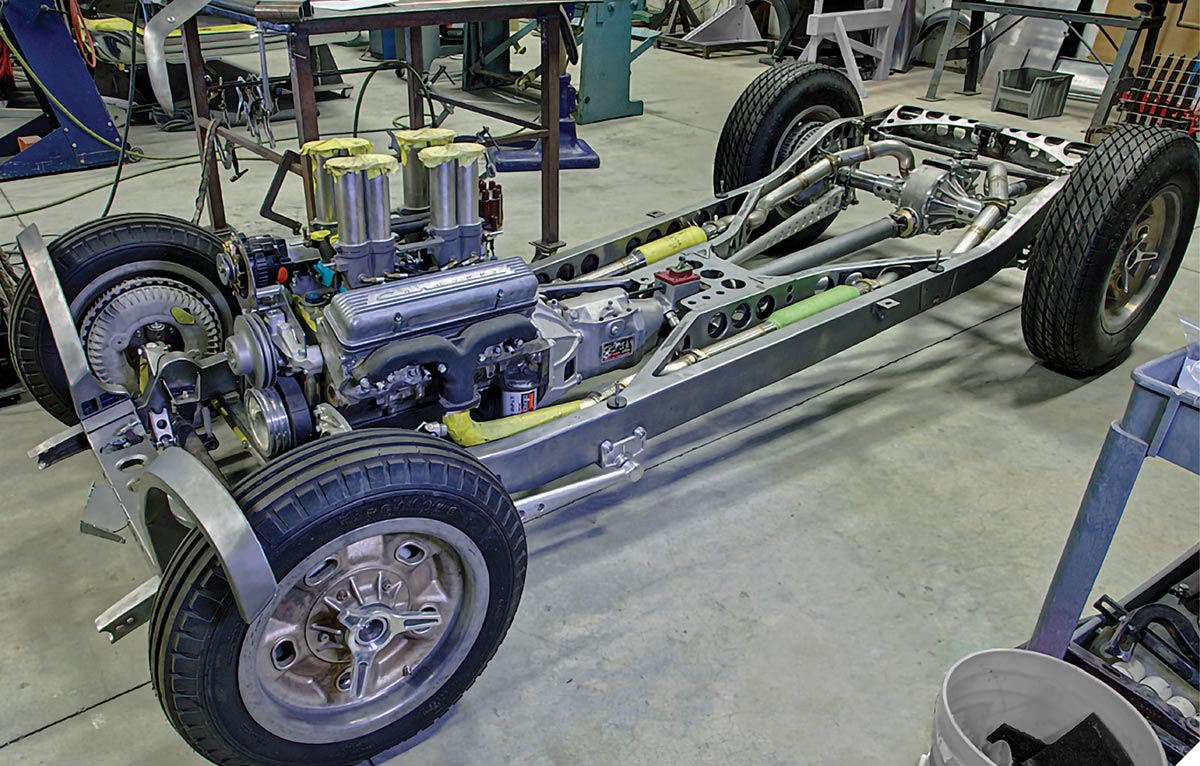

The car has cross torsion bars, both front and rear, with a dropped tube axle in front, and a Winters quick-change in the rear. New boxing plates and a new X-member are fitted to the framerails, liberally perforated with “speed” holes.

Johnson’s Hot Rod Shop’s vintage-looking disc brakes are used on all corners, and their billet radius rods are used front and rear.

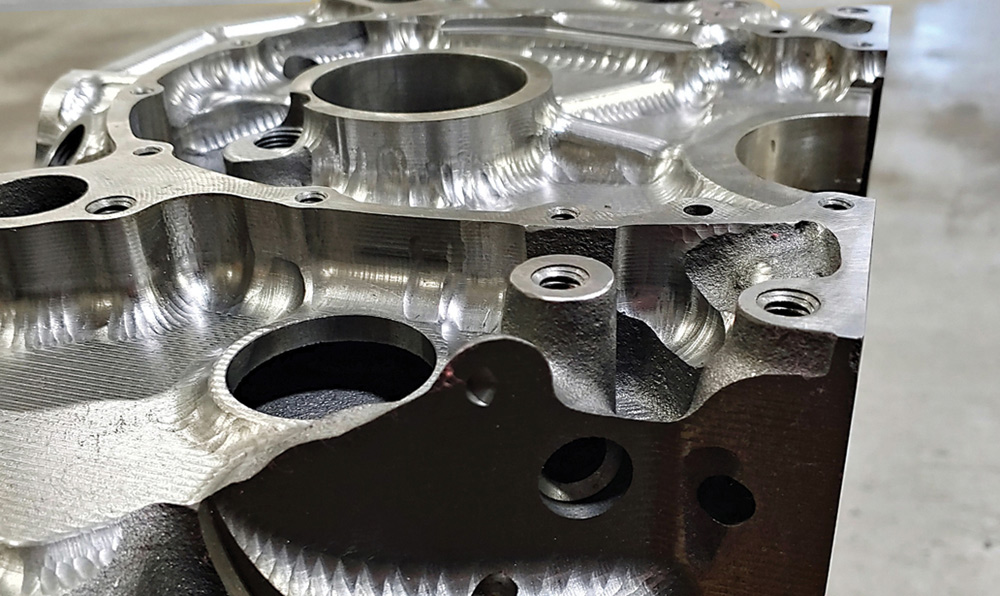

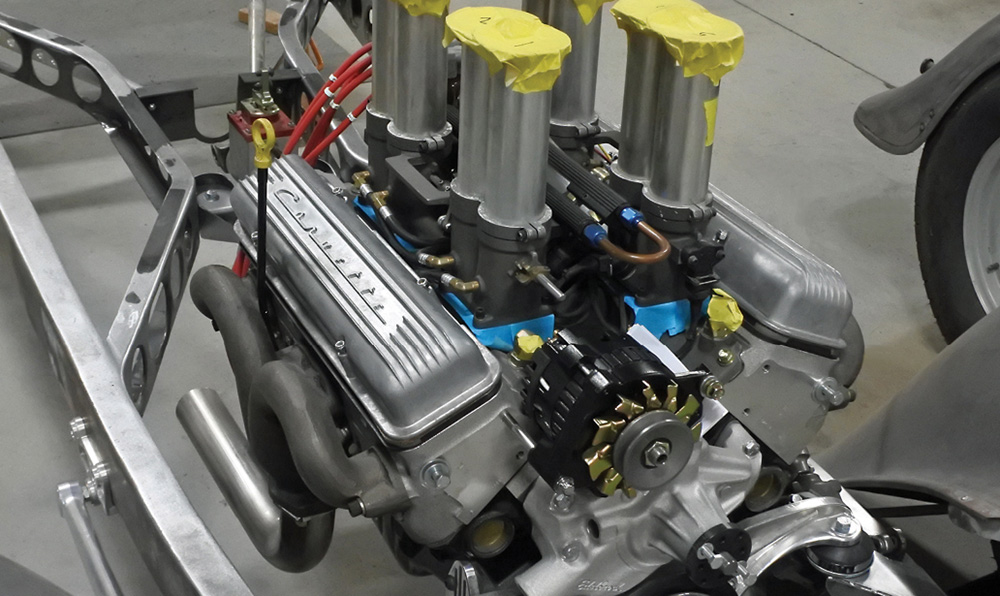

The engine is a potent small-block Chevrolet with aluminum heads featuring a Holley electronic injection and ECU adapted to Hilborn castings and is fitted to a Bowler TKX five-speed transmission. The block was completely CNC machined to smooth the castings, removing any extra mass and unnecessary features. The exhaust is all stainless and is carefully routed through the chassis, so nothing hangs below the framerails.

The Ironworks crew is using CAD design, coupled with 3-D printing and CNC machining to make many of the most challenging components for this build. This technology opens a lot of doors for efficiently designing intricate parts. Once a design is made, it can be printed to make a trial part for fitting and testing before it is CNC machined from billet. It is relatively easy to make changes in the CAD model, so often several iterations of a design will be printed and tested before committing to metal. There is no limit to the intricacy of the details incorporated, and the parts can be made with tolerances simply not possible with hand-fabricated parts. This type of fabrication used to be limited to NASA-level work, but the technology has become much more affordable and user-friendly in recent years.

This first article will focus on the chassis build, and next time we’ll dive in for some of the body modifications. Hang on, we think you’ll love this journey!

VOLUME 4 • ISSUE 29 • 2023