InTheGarageMedia.com

Photography by THE AUTHOR and Courtesy of the Greg Sharp Collection & Tyler Hoare Collection

n part I we tallied the prodigious Tommy Hrones’ body of work, his apprentice years in his uncle’s autobody shop, his roots in Oakland, and his early customs. Here, the Tommy Show unfolds with theatrical flourishes, his collaboration with builders like Joe Bailon, and a gallery of cars bearing his unique accents.

December 1994. Tommy is closing his shop in East Oakland. There’s one last car being masked for final spray. “Oh, hell, he can wait,” Tommy growls. His office is bare, with an unvarnished desk and a filing cabinet. He pulls out the desk drawer, spreading out dozens of snapshots—all young, very attractive women in ’40s-style Betty Grable swimsuits.

Wistfully, he sighs. “Yeah, we had a good time in those days. Go down to Forest Pool in the Santa Cruz mountains.”

The presence of an attractive woman would often put Tommy into motion. In an earlier interview, ’striper Greenwood recalled, “We were up at another shop. Tommy was there with his Triumph and this older man came in with a stunningly beautiful young woman. Tommy jumped right up: ‘Don’t go away. I’ll be right back!’ He tore out down the hill to the nearest flower stand, roared back to the garage, entered at high speed, lay the bike over, slid right up to the young lady, dismounted, and handed her the bouquet.”

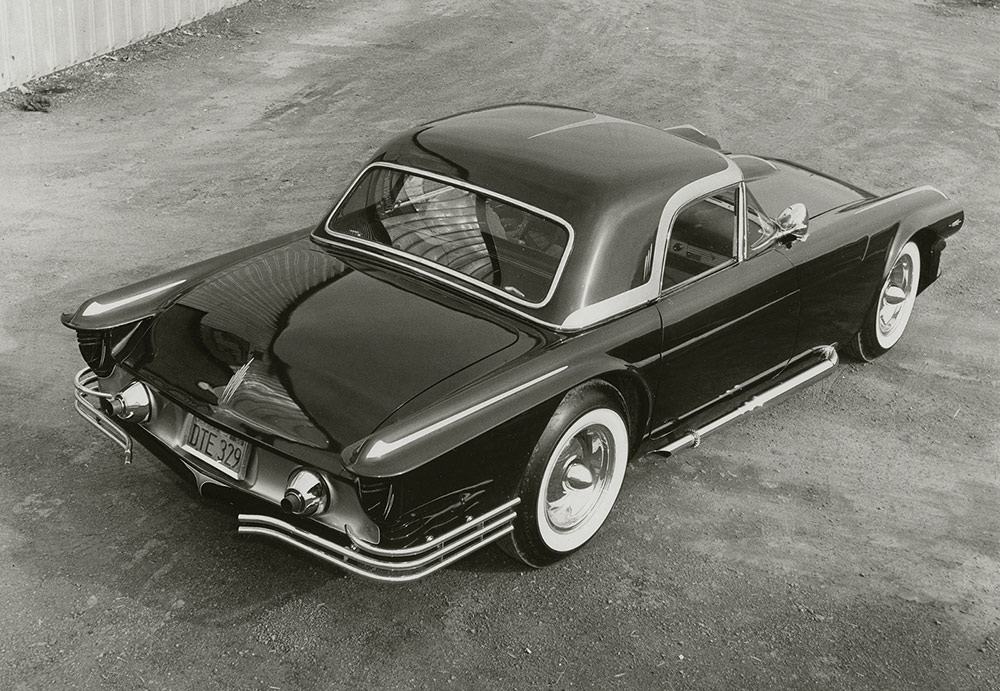

In the ’60s, his reputation could’ve taken him other places, but he chose to work in Oakland where he collaborated with custom car builders like Joe Bailon and a clique of innovative fabricators like Jack Hageman (“He’s the best,” Tommy said in an early interview).

“I did all of Dago’s jet jobs,” he said. “Dago” being Romeo Palamides, a flamboyant Oakland racer/showman who campaigned his “Untouchable” jet dragsters at California strips in the ’60s. “Red, white, and blue, and purple and white. I also sold him a lime yellow ’41 Caddy. I made an Indycar for Jim Hurtubise, purple and silver. I was makin’ good money—$50-$60 a car.”

There was plenty of work for other talented Oakland painters. Red Lee was a ’striper who was a paint judge in early Oakland Roadster Shows. Leroy Suprenaut was a mainline painter for the Strehle Body Shop in Oakland but was also a ’striper with a rare skill in the application of intricate gold leaf. (His work embellishes the Victorian pumper fire engine in the History Gallery of the Oakland Museum). St. John Morton not only ’striped and painted but promoted the art of accent and embellishment.

Tommy could put ascending young artists through the wringer. Great painter Art Himsl of Concord, California, was doing a ’striping demonstration at an early Oakland Roadster Show. It wasn’t going well.

“Man, I was having trouble laying a straight line; it was running late and I was nervous. There was a crowd but in back a booming voice, ‘Hey, kid, havin’ a hard time? Can’t hold at straight line?’ I’d had enough, and turned to the agitator, ‘Here, you do it!’ and handed him the brush. It was The Greek. Zip. Zip. The job was done. He turns and says, ‘Here’s my card kid.’”

Tommy was a sharp observer of human nature and took satisfaction in pranking customers. If someone dare suggest how he do his work, the colors, the lines, he’d do just half the car or kick the customer out. Long ago, the late Jim McLennan, part owner of San Francisco’s legendary Champion Speed Shop—and a leader of the San Francisco hot rodding movement in the ’50s—called in a hurry. Champion’s cherished ’34 Ford pickup was headed to the Oakland Roadster Show the next day. He needed a quick ’stripe job. Tommy showed up and started working; it was late and he feigned fatigue, dribbling a line down the side of the truck’s door. “Oh, oh, I’ll have to do this tomorrow.” McLennan went ballistic: “This (expletive) is supposed to be the greatest and he can’t even do a straight line.” Tommy let it stew; a master of drying time, he finally stepped up, wiped off the offending curve and laid in the line. McLennan and Tommy were friends forever.

In retirement Tommy played a lot of golf, savored a soft ride in one of his many Caddy sedans, and always took time to feed the stray dogs, cats, and pigeons near his Oakland shops. Tommy’s work was art—and it set him apart.

“Tommy’s art has always been in a classical vein: clean, a disciplined line, spare decoration, clear, and well-defined areas of activity and void. Think of the work of the Dutch artist Mondrian,” Phil Linhares says, retired chief curator of art at the Oakland Museum of California and co-curator of the museum’s 1998 exhibition Hot Rods and Customs.

In contrast is the art of rival Von Dutch—the Jackson Pollock of ’stripers! Tommy’s work expressed the hot rod and custom design language of Northern California—think Gene Winfield and the Bay Area Roadster guys. In vivid contrast think George Barris and Ed “Big Daddy” Roth; excess was only the beginning.

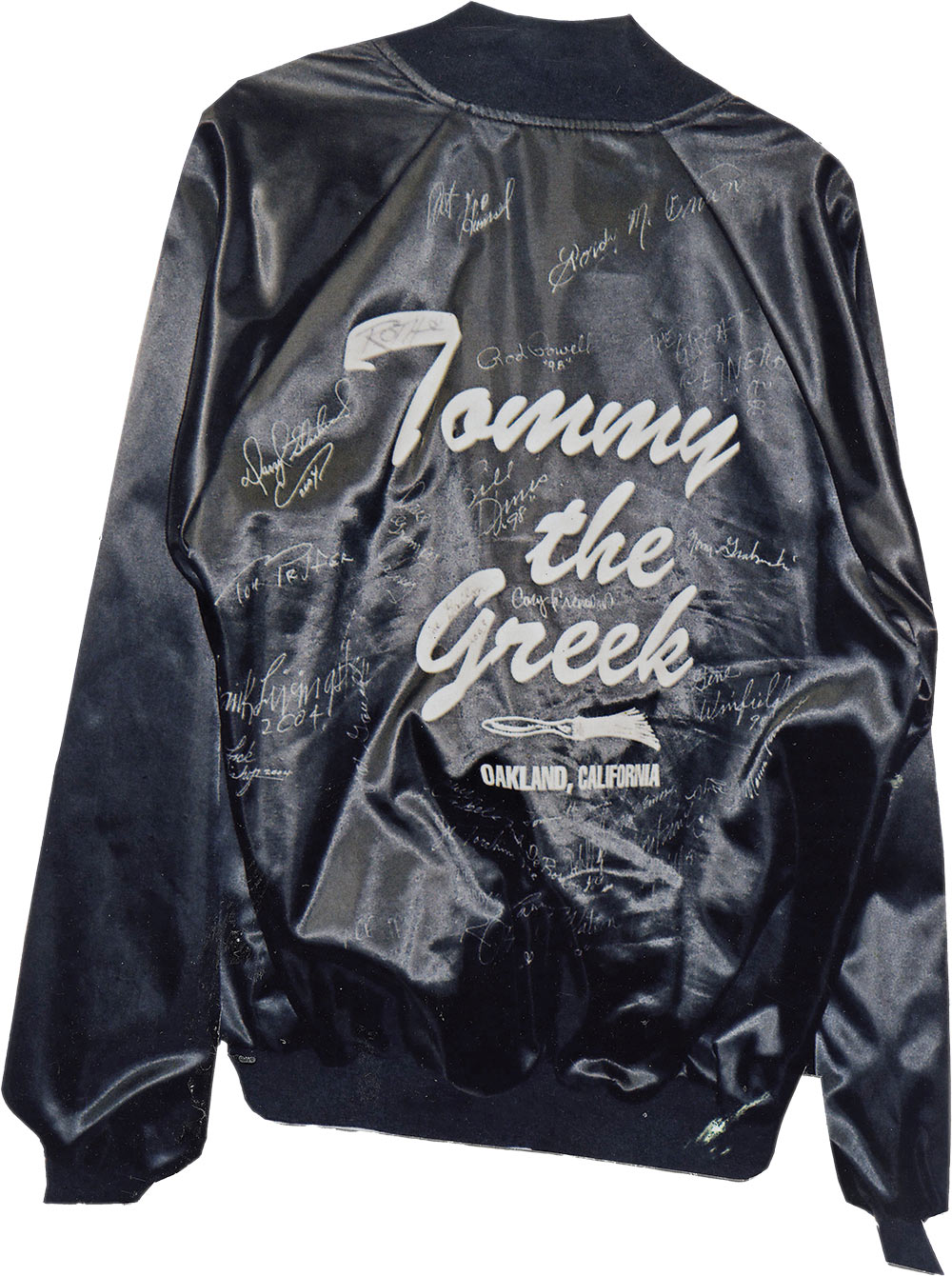

It would be fitting that Tommy’s final act—his January 2002 funeral—would be laden with irony and uproar. His coffin was lavishly ’striped and he was buried with a brush in hand. There were more than 200 loyal East Bay hot rodders and custom car colleagues on hand. Most had known Tommy for decades. The priest recited his incantations and began his eulogy, “Dearly beloved, we are here to honor the life of Jimmy the Greek . . .” Pandemonium. Shouts. Curses. Disruption in the pews. The priest of course corrected his mistake, but the grumbling and mumbling went on.

There was and will forever be only one Tommy the Greek Hrones, master of accent and forever flowing lines that bring the final embellishment to the custom cars and hot rods of our time. (Editor’s note: Tyler James Hoare, a longtime Hrones benefactor, died in January 2023.)