et’s face it, we’ve come to the time in hot rodding’s long history where it’s very rare to find an unmolested early Ford body that doesn’t need a ton of sheetmetal repair work. Sure, there’s the random “barn find” that surfaces from time to time, but the majority of prewar cars that haven’t seen the road in a half century or more are gonna need a lot of TLC. My 1940 Ford coupe is in need of a new replaced sheetmetal floorpan.

Purchased on a lark after my dad forwarded me a link to an online auction, my interest was piqued more out of curiosity than of acquisition. After noticing, on the last day of the auction, that bidding had stalled back on the second day, I thought, “I’ll bid it low. What’s the worst thing that could happen?” Well, the result may not have been the worst thing, but it wasn’t what I was expecting. I won the auction and now needed to get said hunk o’ rust from Wisconsin to California—and STAT as winter was coming quick.

As one is wont when buying a car sight unseen, I carefully inspected every image and decided that worst-case scenario, if I had to simply cut my losses, I could most likely part the car out and break even. That said, I figured that there had to be enough sheetmetal worthy of repair that that situation probably wouldn’t be the case. A few weeks later, when the car arrived on my doorstep, I was pleasantly surprised at the condition of the coupe.

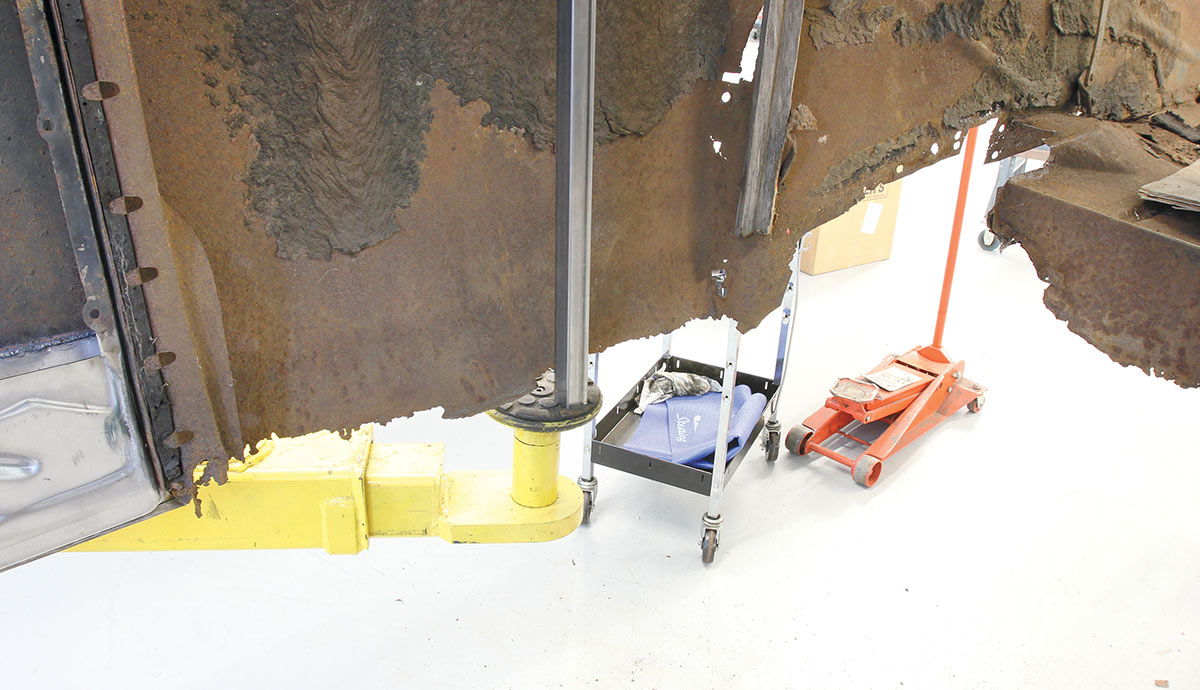

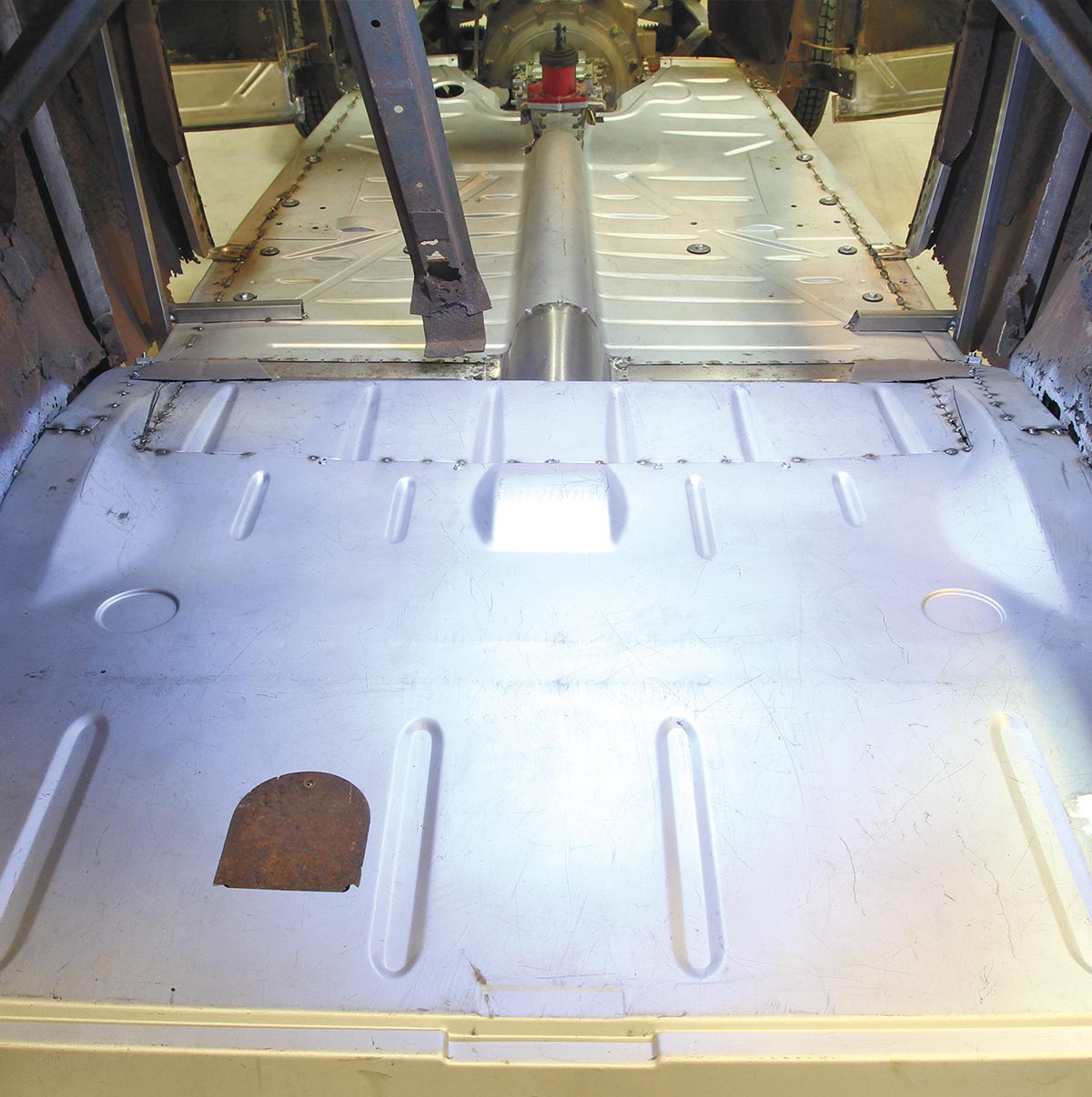

But, that’s not to say the car was in any kind of “restorable” condition upon delivery. As the images clearly showed, the coupe lacked any type of floor, the firewall was damaged beyond repair, and the trunk area also suffered from similar destruction. A decent body otherwise, salvageable sheetmetal and a complete, original chassis made the deal worthwhile, but it was going to be a long road.

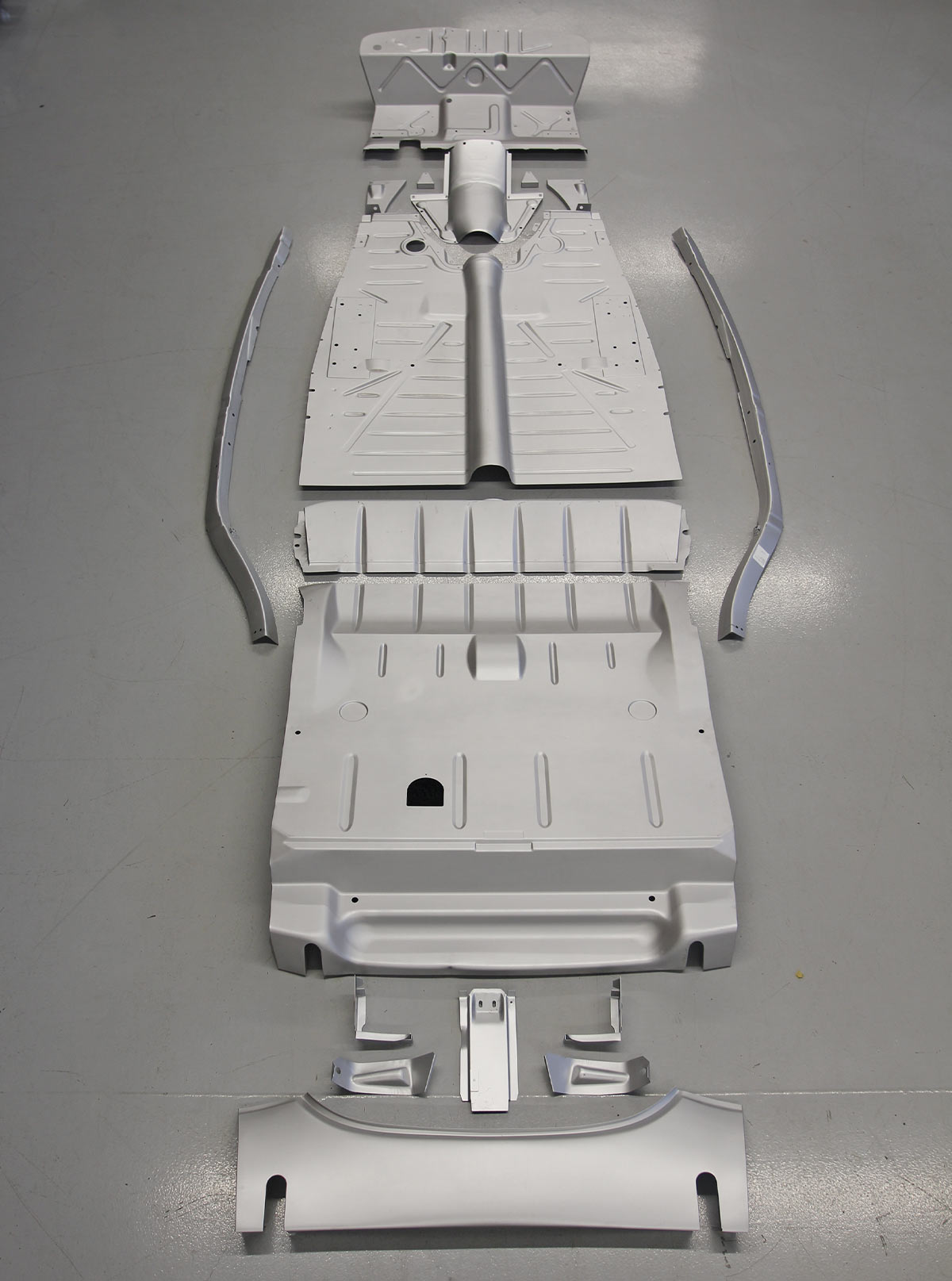

One of the factors that played into me taking the risk of buying a car sight unseen was the fact that I knew what components could be replaced with new. Case in point, I knew that United Pacific carried new main floors, trunk floors, sub rails, under decklid, and firewall replacement panels. Repair panels for the lower rear quarters and lower doors are also available. That alone covers 95 percent of the damage that could be seen. Since the 1940 Ford has been an extremely popular model since its inception, original parts are common, so it wouldn’t be too hard to piece a solid car back together.

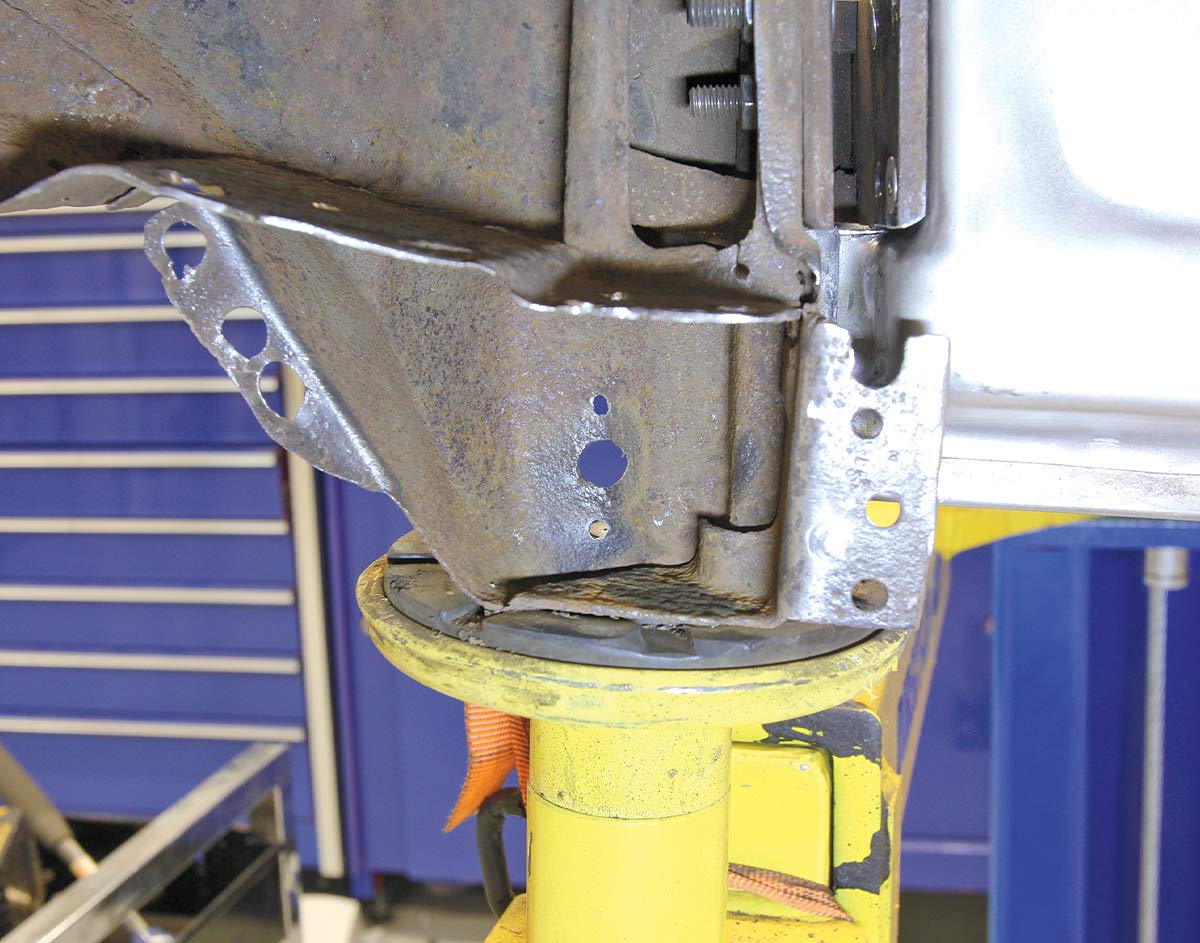

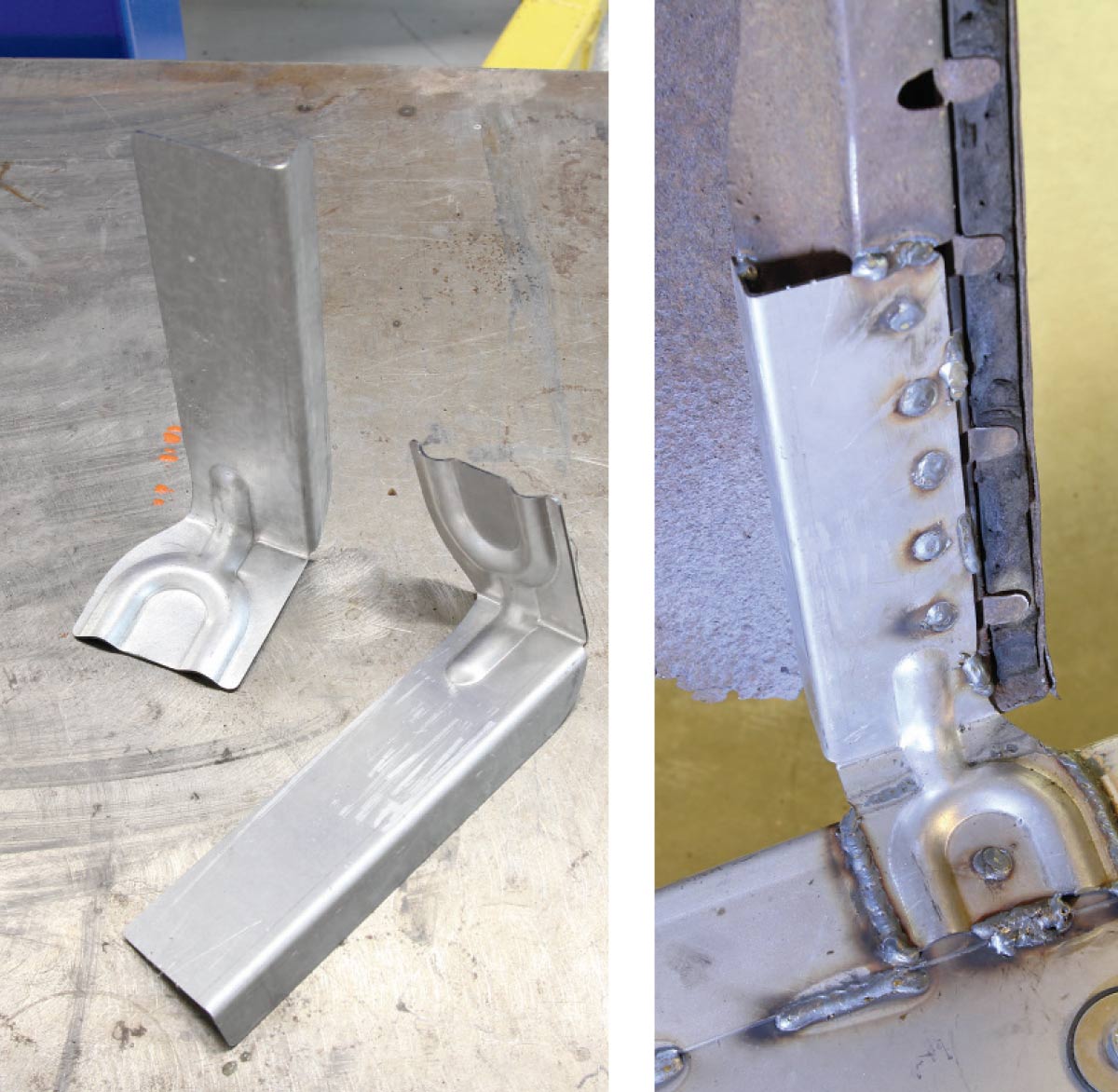

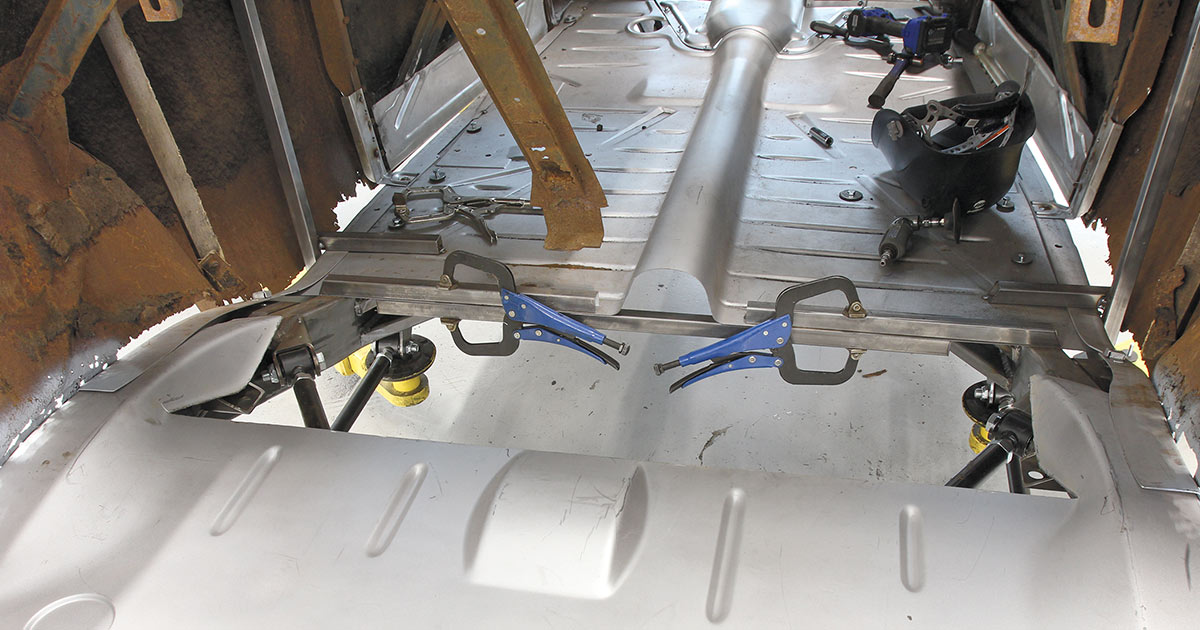

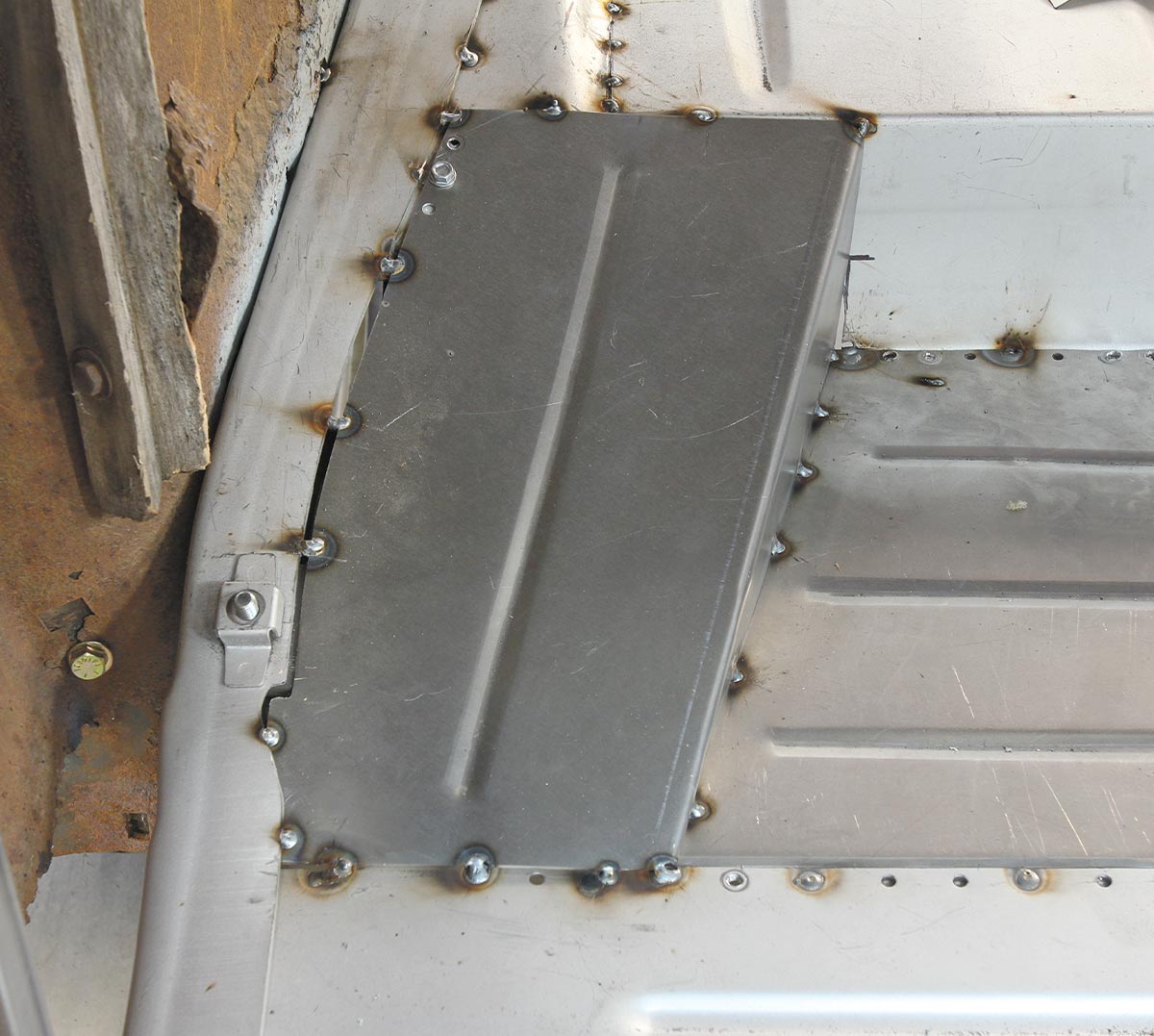

Before we jumped into the fire, however, we decided that it would make more sense to scrap the original chassis and opt for a new roller from Fatman Fabrications. Since the condition of our original frame was unknown, we didn’t want to run the risk of rebuilding the body on a crooked, twisted, or otherwise-damaged frame. After removing the body and rolling the frame out from under, it turned out to be a good decision as the original chassis had a bit of a twist to it and suffered from some pretty serious rot. Cast aside, we began our body repair by placing the new United Pacific sheetmetal on the new Fatman Fabrications chassis using a reproduction body mounting kit. Checked and double-checked for square, we then set our sights on preparing the shell of our body to receive the new floors. One deviation we’ll be making relates to the middle and trunk floor area. United Pacific’s floorpan is designed to replace what Ford called their five-window coupe. This model came with a bench seat with a tilt-up back that allowed access to a compartment underneath a package tray between the seat and the trunk. Our body is what Ford referred to as a “Business Coupe,” which featured a split bench seat up front and rear, fold-down jump seats. This rear seat design has garnered this body style the nickname “Opera Coupe,” though Ford never referred to it by that name. Likewise, the coupe with the package tray is commonly referred to as a “Business Coupe,” which is technically incorrect, although it makes more sense. The difference in the floorpans allows for additional foot room for the jump-seated passengers in the opera-ahem Business Coupe.

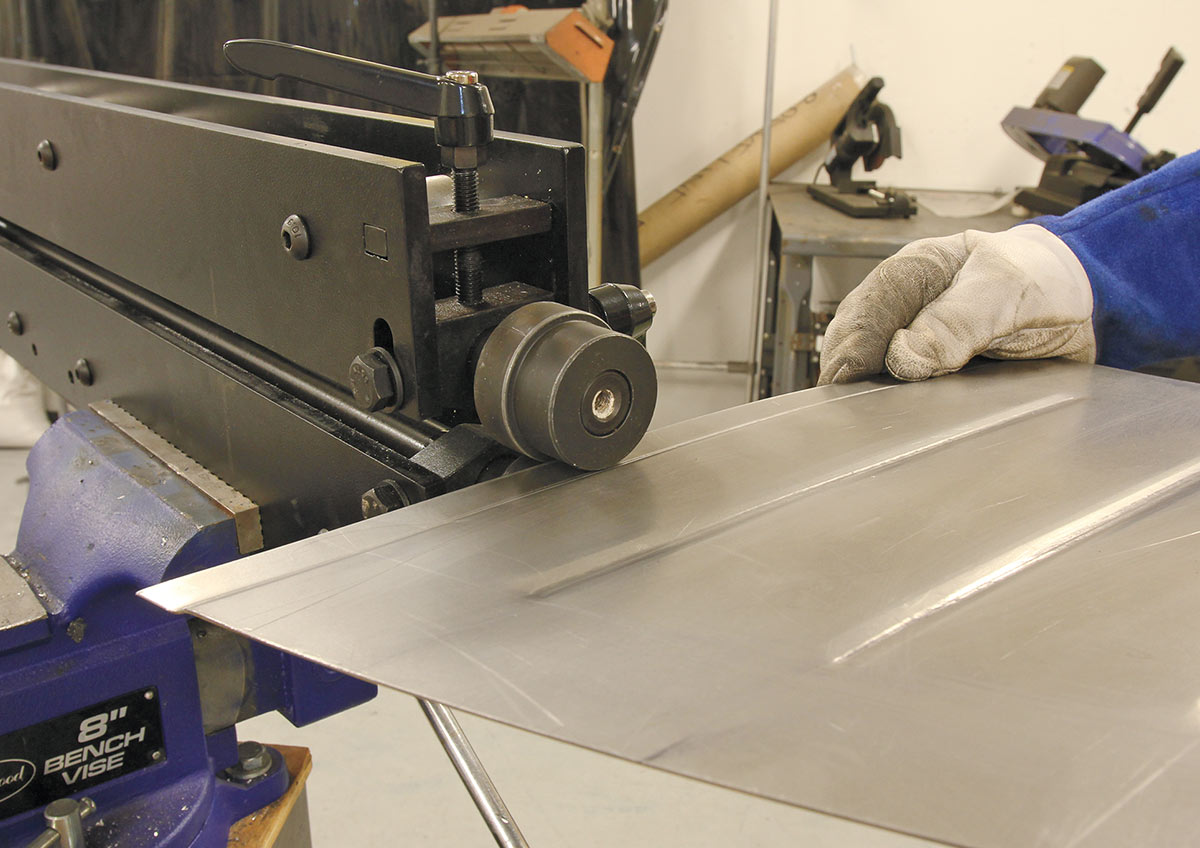

Using similar techniques as those used in the original Ford factory for attaching the sub rails and floorpan, the project turned out to make quick headway. After removing myriad spot welds from the rotting panels that were still attached to the original body, those same spot-weld locations will function to attach the new sheetmetal. Moving slowly and carefully as the new panels were tack welded in place, our original body was starting to return to a much more solid state. Where the B-pillars hung in the breeze, barely allowing the doors to latch, with the new sub rails and floor attached, things were squaring up nicely.

Repairing and replacing floors in a car this large might seem like a daunting task at first—and to be fair, it is a large project—but with the quality of new sheetmetal parts and a patient, watchful eye, a body even as damaged as ours can be brought back to a restorable condition in couple days’ time.

Fatman FabricationS

(704) 545-0369

www.fatmanfab.com

United Pacific

(866) 327-5288

www.upcarparts.com