Photography by THE Author & Courtesy of Speedway Motors

lthough manual transmissions have all but disappeared in new production vehicles, they remain popular with performance enthusiasts who appreciate the greater feeling of control that comes with manually shifting gears.

There are indeed several manual transmission options for Chevy engines, new and vintage. Still, honestly, we’re talking about the old-school Saginaw/Muncie four-speeds and the contemporary TREMEC five- and six-speed gearboxes. Fortunately, with the essentially common bellhousing mounting pattern on everything from vintage 250 inline-6s to the latest LT engines, as well as the plethora of adaption kits, it’s possible to match virtually any Chevy engine with a Muncie or TREMEC transmission and even earlier BorgWarner T5 gearboxes.

An old Muncie rock-crusher, for example, will fit in nearly everything, and aftermarket companies such as Speedway Motors offer bellhousings for the pairing. Still, it lacks the overdrive that makes highway driving much more comfortable with later five- and six-speed transmissions. In the early days of six-speed installations, they typically involved a production-based T56 F-body or Corvette transmission—or even a Viper six-speed, if you could find one.

The T56 is economical for swaps featuring a stock or mostly stock engine, while the stronger Magnum version offers a 700 lb-ft torque rating and comes with 4616 chromoly gears and shafts, triple-cone synchros, and more. It’s sturdy.

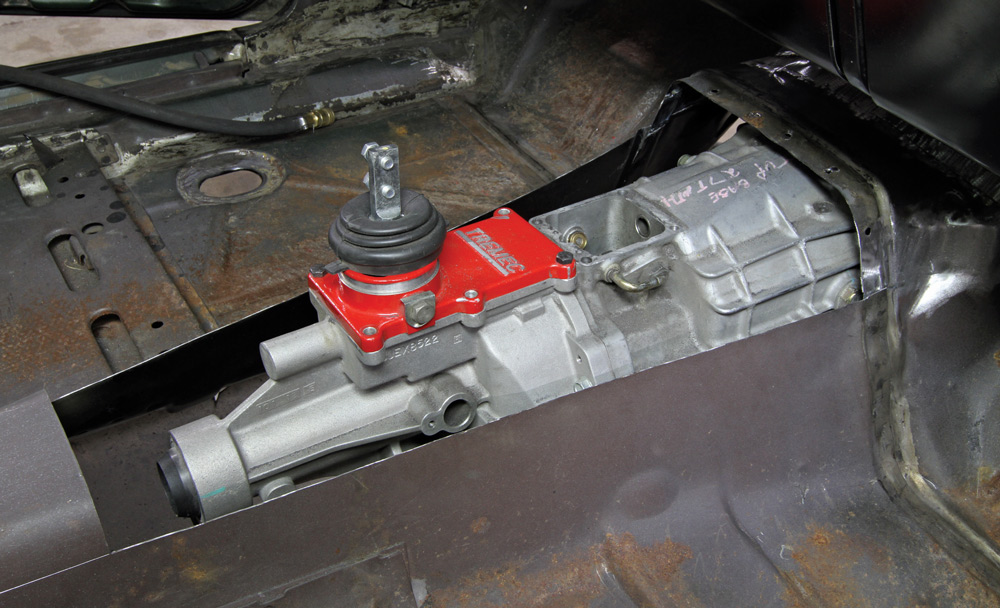

The six-speed transmissions also come with two overdrive gears, which enhances highway driving. It all sounds great, but the hitch is their size. The TREMEC six-speeds are bulky and require transmission tunnel and/or firewall modifications in most vintage vehicles.

The compromise is a slimmer TREMEC five-speed, such as the TKO or TKX. Both have an overdrive top gear and are rated at 600 lb-ft—and while plenty of new TKOs are out there, the TKX has supplanted it in TREMEC’s lineup. The big difference is that, rather than the TKO’s top-loader design, the TKX has an end-load gear design similar to the Magnum six-speed. That allows for a more streamlined case design that will slip into the trans tunnel of just about any vintage Chevy with little or no mods.

The LS blocks have an additional attachment hole at the 12 o’clock position and additional structural oil pan attachments. Still, the bellhousing pattern itself is the same as that of old Chevy engines. The same goes for the even newer LT engines. There are a few applications in which the lower holes for the oil pan will not line up, but the oil pan can be replaced with a production-style pan, or the bolts could be left out of the assembly.

The crucial key to all this compatibility is the bellhousing between the engine and the gearbox itself. The input size and mounting pattern of the transmission need to match. Thankfully, the aftermarket has solutions for all the Chevy engine combinations, including LS/LT engines paired with an older Muncie/Saginaw transmission, vintage V-8s, and six cylinders matched with LS and LT engines.

An important detail to keep in mind is LS/LT crankshafts are 0.400-inch shorter than other Chevy engines in relation to the bellhousing mounting face. A specific pilot bearing from GM (PN 12557583) compensates for the difference and allows the use of a standard-length transmission input shaft.

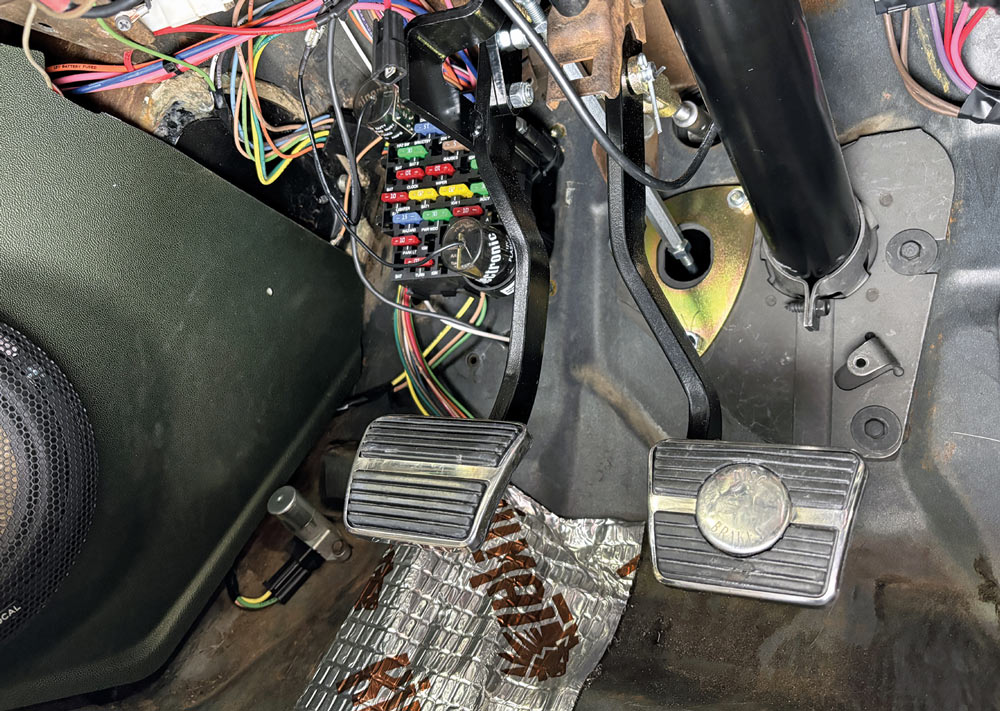

Additional considerations are based on details such as the clutch fork hole location, the Z-bar position, the shifter location, and so on. Still, those are more dependent on the vehicle application. In general terms, the bellhousing will bolt up to essentially every Chevy eight- or six-cylinder engine. Still, for a swap project done right, there are specific bellhousings for the specific engine families and transmissions, each with the proper number of attachment points, bell depth, transmission input, and more.

Most production bellhousings cast aluminum for two straightforward reasons: lower weight and ease of manufacture. Steel bellhousings are heavier but offer a safety advantage over cast aluminum.

That’s not to say aluminum bellhousings aren’t strong. There are a number of aluminum bellhousings out there that meet SFI specs up to 30.1, but they’re typically specialty components designed for racing applications—and they’re priced accordingly. For street-performance vehicles that see perhaps more than the occasional trip down the strip, a steel bellhousing is the cost-effective way to go.

Regardless of the size, it’s also crucial to know whether the engine is internally or externally balanced, as that will dictate the type of flywheel the engine requires. Here’s a quick primer for the V-8 engine:

![]() Early small-block engines with a two-piece rear main seal used 153- and 168-tooth ring gears and were internally balanced. The exception was the 400 engine, which was externally balanced.

Early small-block engines with a two-piece rear main seal used 153- and 168-tooth ring gears and were internally balanced. The exception was the 400 engine, which was externally balanced.

![]() Later, small-blocks with the one-piece rear main seal also used 153- and 168-tooth flywheels. Most of these were externally balanced, but there were a good number of internally balanced engines. Offset weights on the harmonic balancer and flywheel are the clues an engine is externally balanced.

Later, small-blocks with the one-piece rear main seal also used 153- and 168-tooth flywheels. Most of these were externally balanced, but there were a good number of internally balanced engines. Offset weights on the harmonic balancer and flywheel are the clues an engine is externally balanced.

![]() Not surprisingly, all production big-block engines used a 168-tooth flywheel. Earlier engines (pre-454) were internally balanced, while 454 engines up to 1990 had their specific balance. Later, 454/502 engines were externally balanced.

Not surprisingly, all production big-block engines used a 168-tooth flywheel. Earlier engines (pre-454) were internally balanced, while 454 engines up to 1990 had their specific balance. Later, 454/502 engines were externally balanced.

![]() All modern LS and LT engines use 168-tooth flywheels and are internally balanced. The most significant difference between them is with crank flange mounting patterns. Most production engines have a standard six-bolt flange, but the crankshaft on the supercharged LSA, the LSX crate engines, and the latest LT1 engines have eight-bolt patterns, while the supercharged LS9 has its own nine-bolt flange pattern.

All modern LS and LT engines use 168-tooth flywheels and are internally balanced. The most significant difference between them is with crank flange mounting patterns. Most production engines have a standard six-bolt flange, but the crankshaft on the supercharged LSA, the LSX crate engines, and the latest LT1 engines have eight-bolt patterns, while the supercharged LS9 has its own nine-bolt flange pattern.

Remember that factory bellhousings originally used with a 153-tooth flywheel will not fit over a 168-tooth flywheel. An aftermarket bellhousing or a production version for a 168-tooth ring gear must be used.

Also, changing the size of an engine’s flywheel will almost certainly require a different starter.

![]() Four-speed transmission: The Muncie M20 or M21 factory four-speeds matched most small-blocks. The factory bellhousings were aluminum, but for added strength, use Speedway Motors’ steel bellhousing PN 91027000.

Four-speed transmission: The Muncie M20 or M21 factory four-speeds matched most small-blocks. The factory bellhousings were aluminum, but for added strength, use Speedway Motors’ steel bellhousing PN 91027000.

![]() Five-speed transmission: Older BorgWarner T5s and TREMEC TKO-series transmissions work very well, but the latest TKX is the top choice. Use it with Speedway Motors bellhousing PN 91027003.

Five-speed transmission: Older BorgWarner T5s and TREMEC TKO-series transmissions work very well, but the latest TKX is the top choice. Use it with Speedway Motors bellhousing PN 91027003.

![]() Six-speed transmission: Any of the TREMEC T-56-type six-speeds or later TR-6060s will work well with a SBC, but transmission tunnel surgery is almost assured. A steel Quick Time bellhousing from Speedway Motors, PN 91027027, pairs the engine and gearbox.

Six-speed transmission: Any of the TREMEC T-56-type six-speeds or later TR-6060s will work well with a SBC, but transmission tunnel surgery is almost assured. A steel Quick Time bellhousing from Speedway Motors, PN 91027027, pairs the engine and gearbox.

![]() Four-speed transmission: The Muncie M-22 “rock crusher” is the choice with a big-block. It had the highest torque capacity of the factory four-speeds. Use it with Speedway Motors’ steel BBC bellhousing PN 91027000.

Four-speed transmission: The Muncie M-22 “rock crusher” is the choice with a big-block. It had the highest torque capacity of the factory four-speeds. Use it with Speedway Motors’ steel BBC bellhousing PN 91027000.

![]() Five-speed transmission: The same Speedway Motors steel bellhousing PN 91027000 can also be used to match a big-block with TREMEC five-speeds, but their torque capacity peaks at 600 lb-ft.

Five-speed transmission: The same Speedway Motors steel bellhousing PN 91027000 can also be used to match a big-block with TREMEC five-speeds, but their torque capacity peaks at 600 lb-ft.

![]() Six-speed transmission: A TREMEC T-56 transmission is the preferred pairing with a big-block, because of its robust 700 lb-ft torque capacity. Similar to the small-block application, a steel Quick Time bellhousing from Speedway Motors, PN 91027027, pairs the engine and gearbox.

Six-speed transmission: A TREMEC T-56 transmission is the preferred pairing with a big-block, because of its robust 700 lb-ft torque capacity. Similar to the small-block application, a steel Quick Time bellhousing from Speedway Motors, PN 91027027, pairs the engine and gearbox.

SOURCE

SOURCE