Modern Rodding TECH

InTheGarageMedia.com

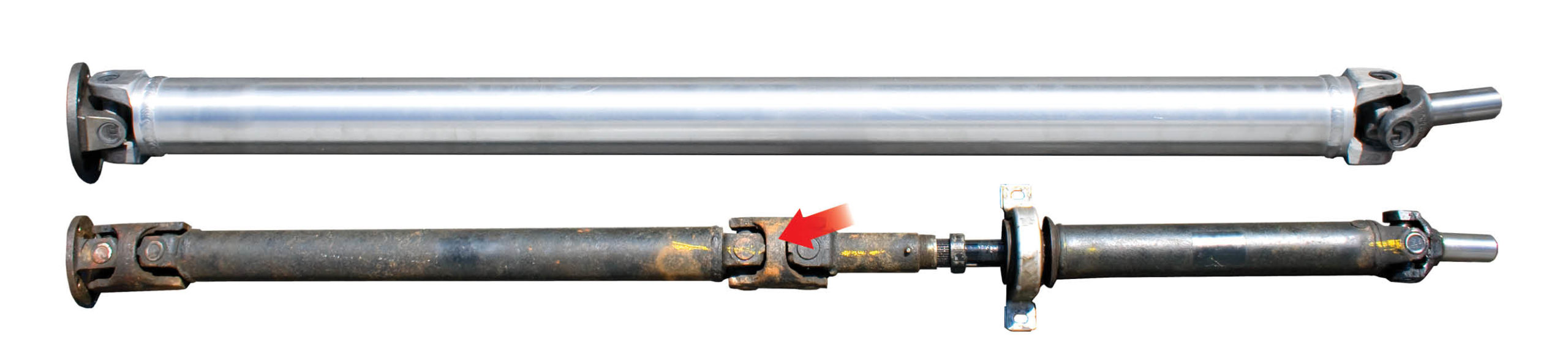

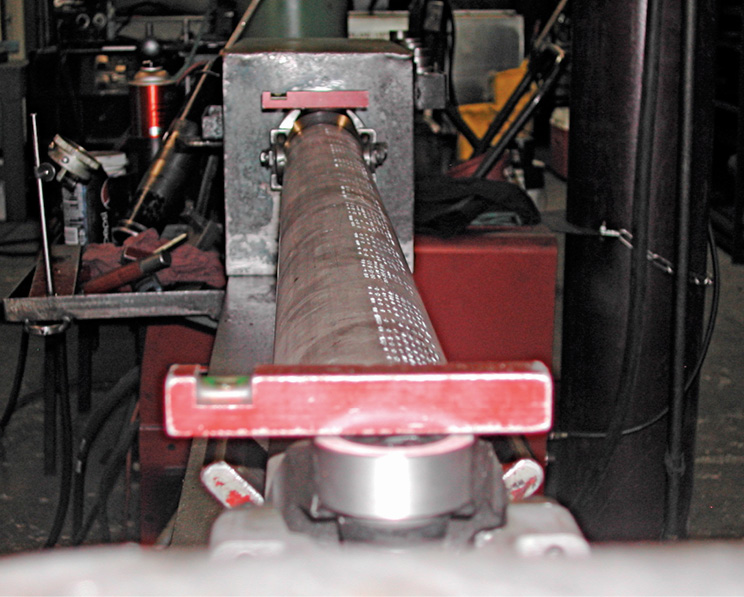

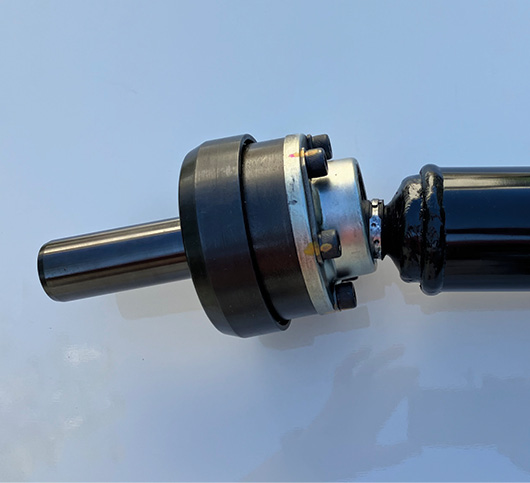

1. This comes under the heading of “stuff happens.” Too much power and an inadequate driveshaft and this is the result.

DRIVESHAFT

DILEMMAS

Choosing and Installing Driveline Components

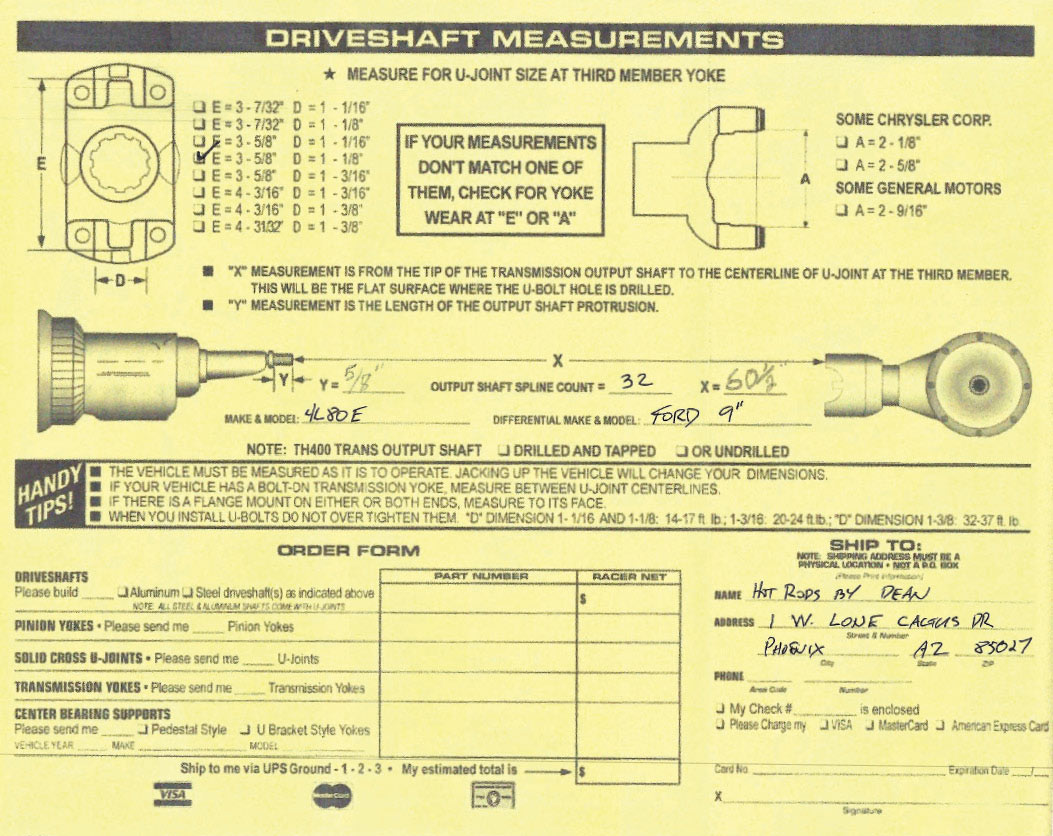

By Ron Ceridono  Photography by The Author & Brian Brennan

Photography by The Author & Brian Brennan

t’s been said that “the devil is in the details,” which is another way of saying that many things are more complicated than they appear and overlooking all the factors involved are sure to cause problems. That more or less describes building a hot rod in general and is especially true when choosing and installing drivetrain components.

Drivelines seem simple enough: they connect the transmission to the differential. The universal joint accommodates the changes in driveshaft angle as the suspension moves up and down. A slip joint absorbs changes in the distance between the transmission and the differential as the axle housing moves up and down and rotates during acceleration and braking. But while none of that seems all that complicated, the wrong parts and/or improper installation can cause problems ranging from an annoying vibration to total failure that may result in a crashed car and injured occupants.

Mark A. Byford P.E. who is an expert on driveline components and design, tells us the universal joint as we know it (technically described as a Cardan-style joint) was designed in 1545 by Gerolamo Cardano and the first working unit was produced by Robert Hooke in 1676, so they’ve been around for a while and the same issues that plagued them then exist today. As Byford describes its operation, “When a Cardan-style joint is operated at an angle, non-uniform motion output is generated, which produces a variety of unwanted vibrations.” Basically, that means as the U-joint operates at an angle, the ends of the cross where the bearings attach travel in an ellipse. Greg Frick of Inland Empire Driveline (IEDL) adds, “For the joint to rotate through the ellipse it must speed up and slow down twice per revolution. As the angle of operation increases the abruptness of the speed change also increases.” Although it seems driveshaft vibration is inevitable, in reality, with a pair of U-joints, the speed variation of one is canceled out by the other. But regardless of how well this is done, the driveshaft is pulsating twice per revolution all the time. The trick to compensating for this is to have the U-joint angles as close to the same as possible.

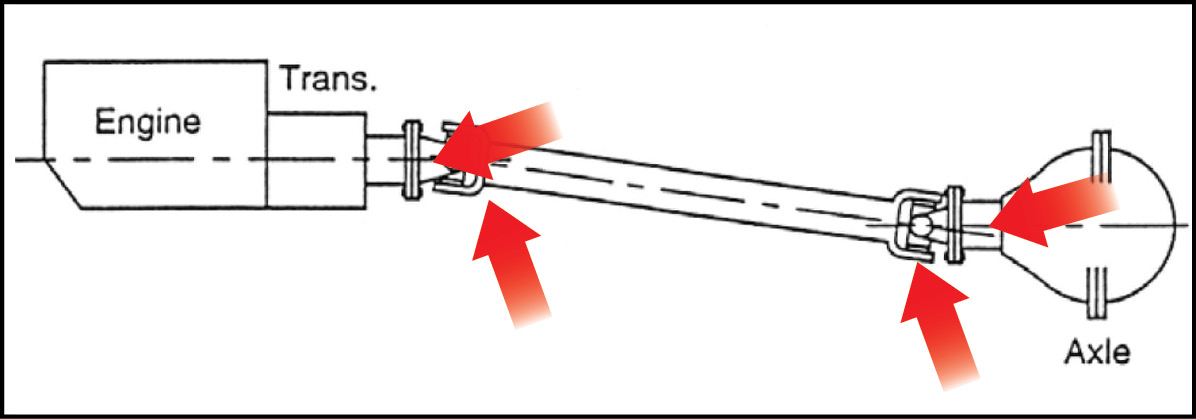

First the transmission’s output shaft and the rearend’s pinion shaft should be parallel. That means if the transmission points down 3 degrees, the pinion should point up 3 degrees, which ensures the motion of U-joints cancel each other. Frick points out, “The objective is to add the angles up to equal 0.” That is to say, visualize the output shaft pointing down 3 degrees (which is considered negative) and the pinion pointing up 3 degrees (which is considered positive); those numbers cancel each other out and the working angle is 0. The second factor to consider is the slope of the driveshaft that determines the operating angle of the U-joints. Frick advises that U-joints are designed to have their maximum life operating at 5 degrees or less, however his experience has shown hot rodders will feel angles sharper than 3 degrees.

Another consideration is the angle of the driveshaft horizontally. Some hot rods, such as highboys where the axle housing is visible, will have the axle housing offset to center it under the car for aesthetic reasons. In that case the operating angle must be checked in the horizontal plane as well as the vertical.

U-joints are obviously critical driveline components and they come in a variety of sizes. The 1310 series is the most common U-joint for automotive use and is still found on original equipment applications. Caps are 1.062 inches in diameter, width is 3.219 inches. The 1330 series is also very common and used on OE production. Caps are the same outside diameter as the 1310 at 1.0625 inches in diameter but the cross is larger, width is 3.622 inches. For a high-performance upgrade, the 1350 series are often used. The cross is the same width as the 1330 but the bearing caps and trunions that they pivot on are larger for increased strength. Caps are 1.188 inches in diameter, width is 3.622 inches

For those applications where the driveshaft and transmission or rear end yokes are different sizes, conversion U-joints are available. These are the common combinations from Spicer and the corresponding part numbers:

1310 ÷ 1350 = Spicer 5 – 460X

1310 ÷ 1330 = Spicer 5 – 134X

1330 ÷ 1350 = Spicer 5 – 648X

Another consideration when selecting U-joints is the difference between those that can be lubricated with a zerk fitting and the sealed type that don’t require maintenance. Frick recommends the sealed style—the improved seals eliminate the loss of lubricant and the lack of passageways to distribute grease improves strength.

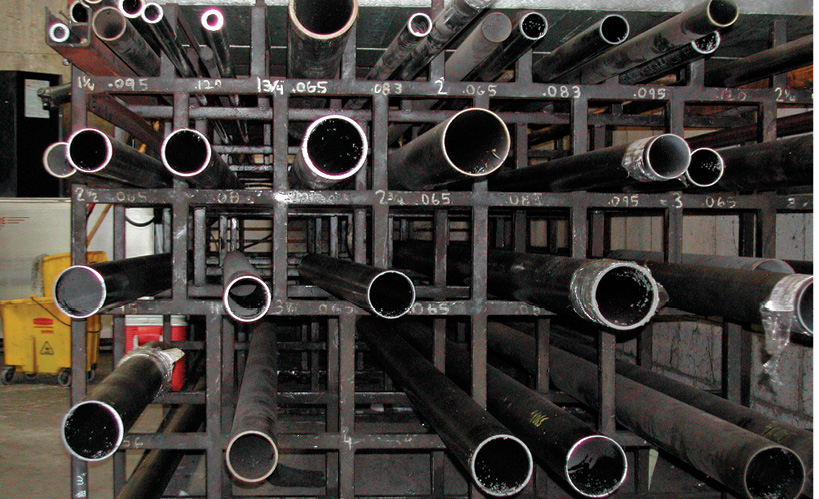

When it comes to driveshafts, they are made from a variety of materials, including, steel, aluminum, carbon fiber, and a hybrid combination of carbon-fiber–wrapped aluminum. Regardless of the material used, an important consideration is something called critical speed, or the combination of driveshaft diameter, length, and rpm at which it becomes unstable—and that can lead to not only vibration but complete failure. To prevent such problems, IEDL will design a driveshaft with half of critical speed in mind as a built-in safety factor. As an example, they limit the length of a driveshaft with a 3-inch-diameter tube and 0.083-inch wall thickness to 52 inches. A 3-1/2-inch, 0.083 tube is used for 56-inch ’shafts and 4-inch 0.083-tubing is good for up to 62-inch driveshafts. Beyond 62 inches in length Frick recommends using two-piece shafts with a center support to ward off the “whip” that can be caused by approaching critical speed. Because of the two per revolution pulsating of the driveshaft it will become excited at half the calculated critical speed, resulting in a very mysterious, narrow mile per hour band of vibration.

Another factor that enters into driveshaft requirements is the transmission used. Frick gives the following example: “In the ’60s, ’70s, and even ’80s there were factory driveshafts that are now considered too long. The Chevelle is a good example. These cars were just fine as built but now run into vibration issues when the engine, or especially the transmission, is changed. Higher torque is available through more gears than the driveline was originally designed for. Overdrive transmissions now slow engine rpm and raise torque demands for the same road speed previously run in direct drive. It is here that the half critical issue is encountered. The driveshaft must now grow from the OEM 3 inches in diameter to 3-1/2 diameter to keep up with the mechanical changes.

Unfortunately, there are some cases in which there are driveline alignment problems that cannot be easily resolved without extensive modifications to the car’s chassis. However, for every problem there is a solution, and in this situation, IEDL offers the apply named “Solution” driveline that won the prestigious best product award in its category at the 2022 NSRA Street Rod Nationals.

According to Frick, by using a true constant velocity joint the angle problem often found with overdrive transmission installations is solved. The issue generally results from the long transmission’s output shaft being below the pinion yoke, causing the driveshaft to go up toward the rearend. As a result, the angle through the front U-joint grows to unacceptable levels, causing greater pulsating vibrations. Of course, misalignment of the transmission’s output shaft and the pinion that can’t be easily corrected can also be cured with the Solution.

The new Solution is currently available in custom steel shafts for use with 27-spline GM PG, TH350, 700-R4, 4L60, 4L60E, 4L65; the 32-spline TH400, 4L80, 4L85; and Gear Vendors overdrive units. Also available are the 31-spline Ford C-6 and Top Loader, and TREMEC TKO, TKX, and Magnum transmissions.

While drivelines are more complicated than they seem, ordering one from IEDL is as simple as it can be. Fill out their order form with the required measurements, then follow our installation recommendations for the various angles involved and those in the IEDL Powertrain Set Up Guide, and a custom driveline will be delivered to your door. That’s the way to eliminate the devil in the details.

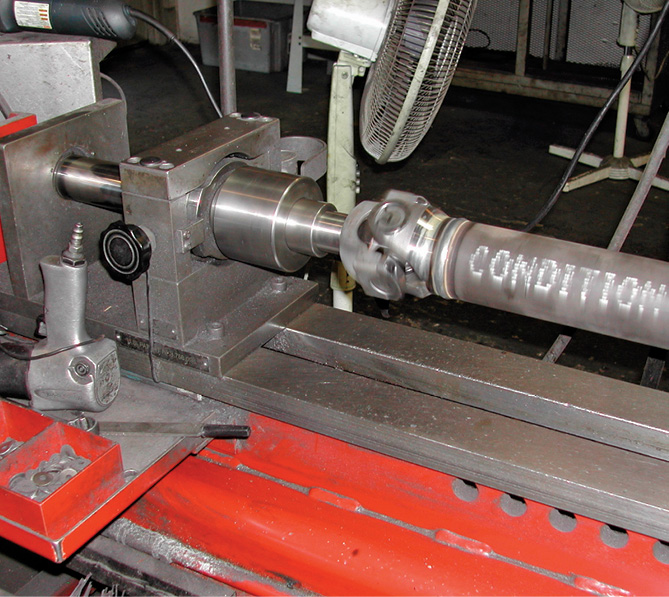

2. IEDL’s steel driveshafts are made from 1026 drawn tubing that is stronger, straighter, and rounder than the cold rolled tubing common in original-equipment driveshafts. Computer-assisted design programs are used to predict critical speeds that determine allowable shaft lengths.

3. IEDL aluminum driveshafts are fabricated from custom-drawn 6061-T6 DOM aluminum tubes with 6061-T6 aluminum forged weld yokes. IEDL have passed Spicer’s grueling dynamic reverse torsion testing, qualifying them as an authorized aluminum shaft builder.

4. A comparison of a single and two-piece driveshaft. As designers reduced ride heights in ’60s driveshafts (with delete) a “double Cardan” joint (arrow) appeared to solve angular problems caused by lowering the car (’58-64 Chevrolets used the two-piece, small-diameter driveshaft shown).

5. A unique U-joint is the ball and trunnion design (arrow) used by Studebaker and the Chrysler Corporation into the late ’60s—it also functioned as slip joint to accommodate changes in driveshaft length.

6. IEDL uses this order form to produce custom driveshafts. It includes U-joint requirements and the necessary dimensions to determine driveshaft length.

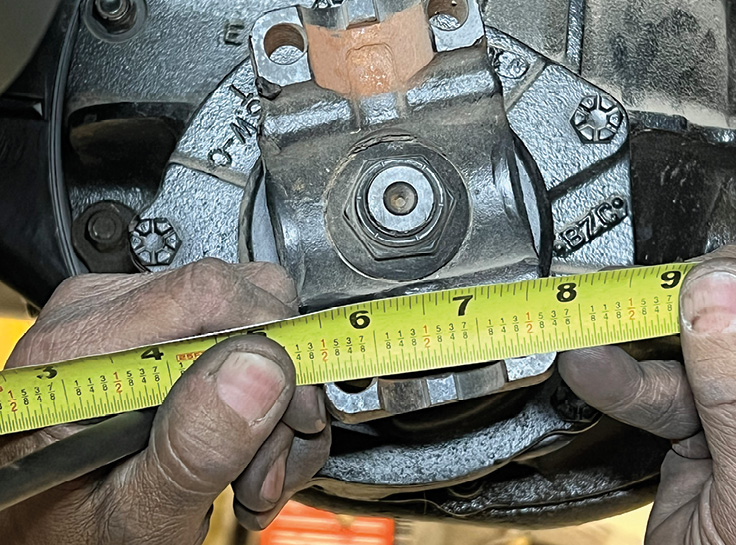

9. To determine the U-joint required, the diameter of the cups is established by measuring the recess in the yoke.

10. Finally the width of the U-joint is established by measuring the distance between the locating tabs (or retainer clip grooves) on the pinion flange.

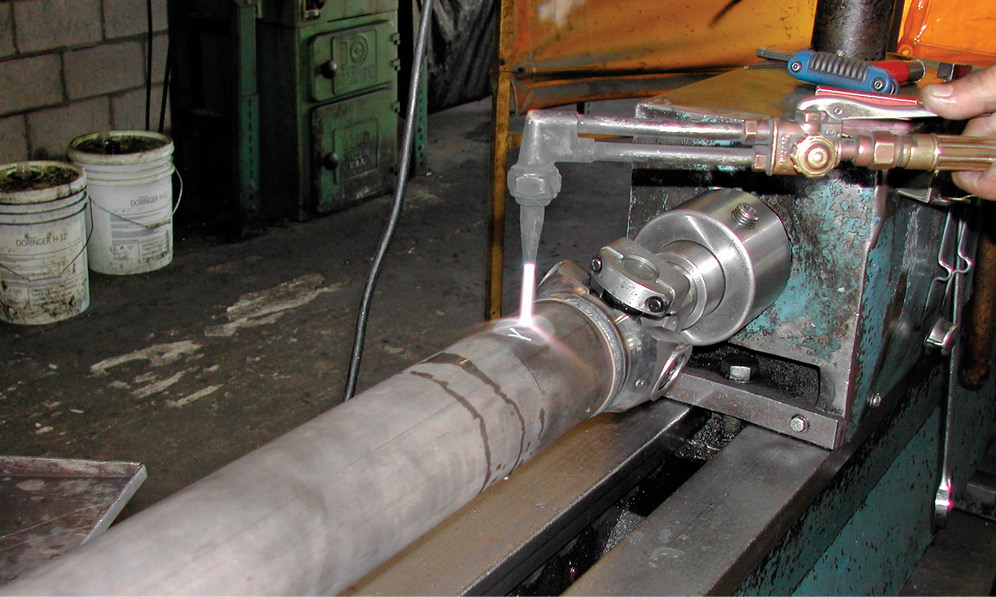

13. For smooth, vibration-free operation, all IEDL driveshafts are balanced after assembly.

15. Here are two broken U-joints. It’s arguable that greaseable U-joints are more prone to failure than the sealed type in high-performance applications due to the lubricant passages.

17. To ensure driveshaft angles are within specifications Frick recommends placing an angle finder on a machined surface such as the starter mount as the output shaft may droop and cause an inaccurate reading.

21. Speedway Motors pinion shims are available in 2 and 4 degrees. Here they have been used in conjunction with lowering blocks.

22. IEDL’s “Solution” driveshaft uses a constant velocity front U-joint rather than the conventional Cardan style. As the name implies, there is no change is rotational speed with a CV joint, which eliminates the vibration problem that can occur with Cardan U-joints when the operating angles are unequal.

SOURCES

SOURCESVOLUME 4 • ISSUE 29 • 2023