Photography by THE AUTHOR

Photography by THE AUTHORur project 1936 phaeton is making steady progress. Like most things in hot rodding, the dashboard project has taken on a life of its own. We could have installed gauges in the existing factory holes, but that would have been way too easy, or as one hot rod sage once told me, “Anything worth doing is worth overdoing.” So, the dashboard modification involved shortening the glovebox (Modern Rodding Aug. ’22), modifying the 1935 Ford hood trim, and, finally, building an entirely new center panel.

We bought an N.O.S. 1947 Ford speedometer and clock at a swap meet. From there we hit speedwaymotors.com to order some traditional-style, black S-W gauges to go with our non-winged 1961 S-W tachometer. We had the clock converted to a 12V and serviced by The Clock Works (clockwks.com).

We enlarged the original speedometer opening and added 3/8 inch to the bottom of the dash to facilitate the larger 1947 speedo. That extra depth was added using a piece of 1×3/16-inch flat stock to form a new bottom profile on the dashboard. This process eliminated the original lower notch in the dashboard. This piece of flat stock defined the new bottom profile and connected the two ends of the dash, allowing us to remove the original center sheetmetal from the dash.

The original gauge opening on the left side of the speedometer was partially filled and then recut to hold the tachometer. The left gauge in a 1936 phaeton dash always seemed too high, so we brought it down to our new centerline.

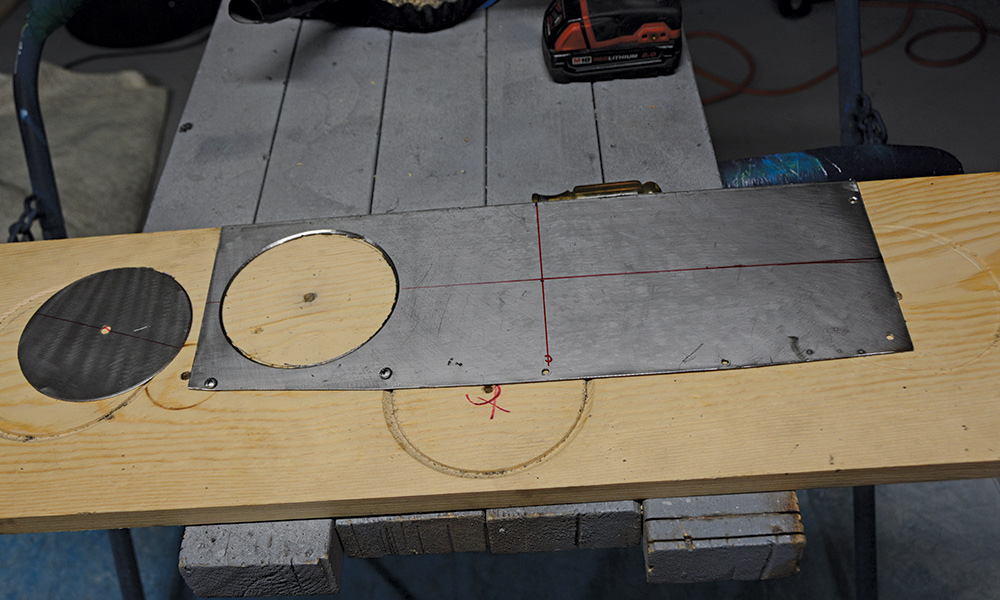

Next, we cut a piece of 18-gauge steel to fit between the speedometer and the shortened glovebox. A metal brake put the desired 90-degree bend on the bottom while the panel’s top extended up to the top of the dashboard. This new panel was held in place with sheetmetal screws while we laid out the design for the dash. We wanted the dashboard to look “old-school complicated” with multiple switches, lights, trim, and gauges. We knew the clock’s position would be on the opposite end from the speedometer, next to the glovebox. After spending considerable time finding the horizontal center of the dash, we marked the clock’s location, removed the panel, and cut the hole for the clock using a fly-cutter in our less-than-precise drill press we purchased 53 years ago. Most gauges utilize a flange and mount from the front of the panel; 1947 Ford gauges mount from behind, protruding through the holes, so the holes must be precise. Filing the new openings gave us an excellent fit.

With the two big gauges mounted, we now knew how much space was between them for our four S-W gauges. Careful measuring kept things evenly spaced and on the centerline. For purely aesthetic reasons, we left slightly more space between the two end gauges and the large gauges, with an equal distance between the four small gauges.

Next, we positioned the three jeweled indicator lights we removed from an ancient dash insert hanging from our shop wall. Finally, we marked the location for the five switches and drilled the proper size hole for each switch, and no two were the same size. We had a pull button starter, headlight switch, horn, power port (formally known as a cigarette lighter), and the choke rod. Vintage-style knobs from SO-CAL Speed Shop keep the vintage theme.

Once again, the panel was removed, and the same sheetmetal screws now held the panel in place on a piece of wood while we cut the holes. The S-W gauge holes were cut with a hole saw, while the light and switch holes had their respective drill sizes. We cannot overemphasize how important measuring and alignment are on the dashboard. Remember, you will look at this whenever you sit in the car. Confident that all spacing was correct, we screwed the new panel back in place and TIG welded the centersection to the two ends.

We formed the 1935 Ford hood side trim to fit between the gauges and along the bottom of the dashboard, and then it was time for typical bodywork and paint. We picked a non-metallic, gray/blue color from the PPG fleet color palette and used their Delfleet Essential paint (our new favorite, go-to paint). The paint flowed out perfectly and required no buffing. We also painted our genuine Stewart-Warner Southwind heater to match, with a gold accent on the bottom. A Vintage Air heater supplies the hot air to our unit.

Next, we installed all components and turned the dash over to complete the wiring, forming a harness long enough to merge with the existing wiring from the fuse panel. A piece of fender welting was used between the top of the dash and the cowl, and the dashboard was in place for the last time.

However, we were unsatisfied with the minute gap around the speedometer and the clock required for the rear-mounted gauges. We came up with a unique solution. We went online (All World Machinery Supply) and located an O-ring that was slightly smaller than 1/16-inch (1.78mm) thick by just under 4-3/4 inches (120.37mm) in diameter. This stretched nicely over the large gauge bezels and provided the perfect seal around the gauges. Our trim pieces hold the rubber O-rings in place, but a simple drop of super glue could be used if needed. With that little trick, we had perfect fitting gauges.

We are very pleased with the final look of the dashboard. It combines vintage, art deco–style gauges with traditional hot rod bits. We like to think these same parts could have been combined in the late 1950s by any enterprising hot rodder or customizer seeking to modernize with “almost-factory”-appearing gauges combined with hot rod gauges.

Was forming this dash a lot of work? Absolutely. But one thing is sure: The effort will pay off every time we slide behind the wheel. Now we are one step closer to finally seeing that speedometer needle move.

SOURCES

SOURCES