1. Nick Sinioris at Hot Rods by Dean carefully planned out his work and then worked his plan–how’s that for a novel approach!

Photography by Brian Brennan

Photography by Brian Brennanhe world really doesn’t need yet another top chop story—or so I thought. Then ol’ Editor Brian Brennan visited Dean Livermore at Hot Rods by Dean and brought home these photos on the chopping of a ’33 Ford DeLuxe coupe.

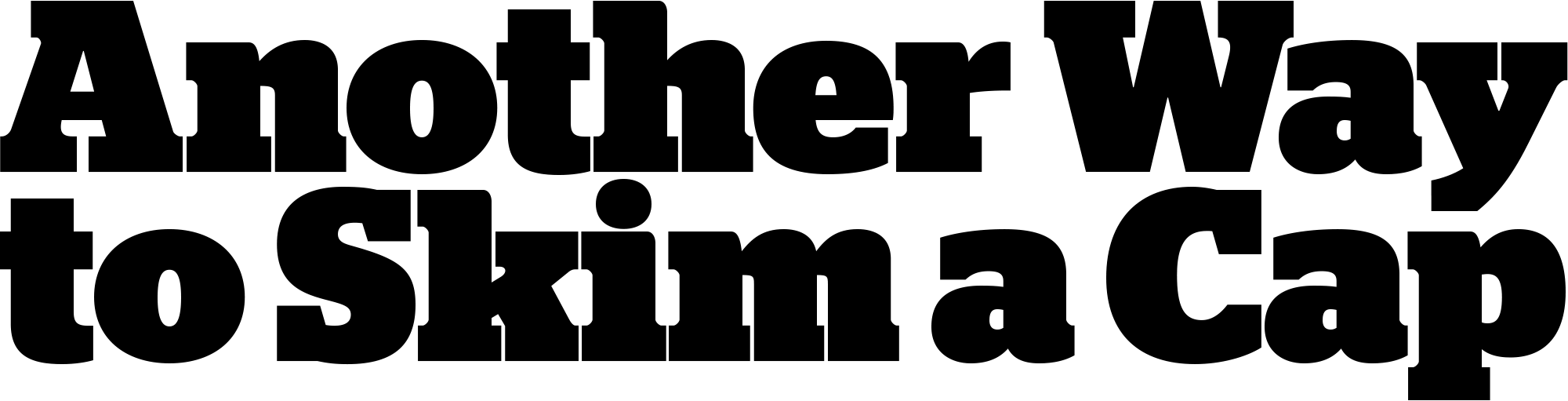

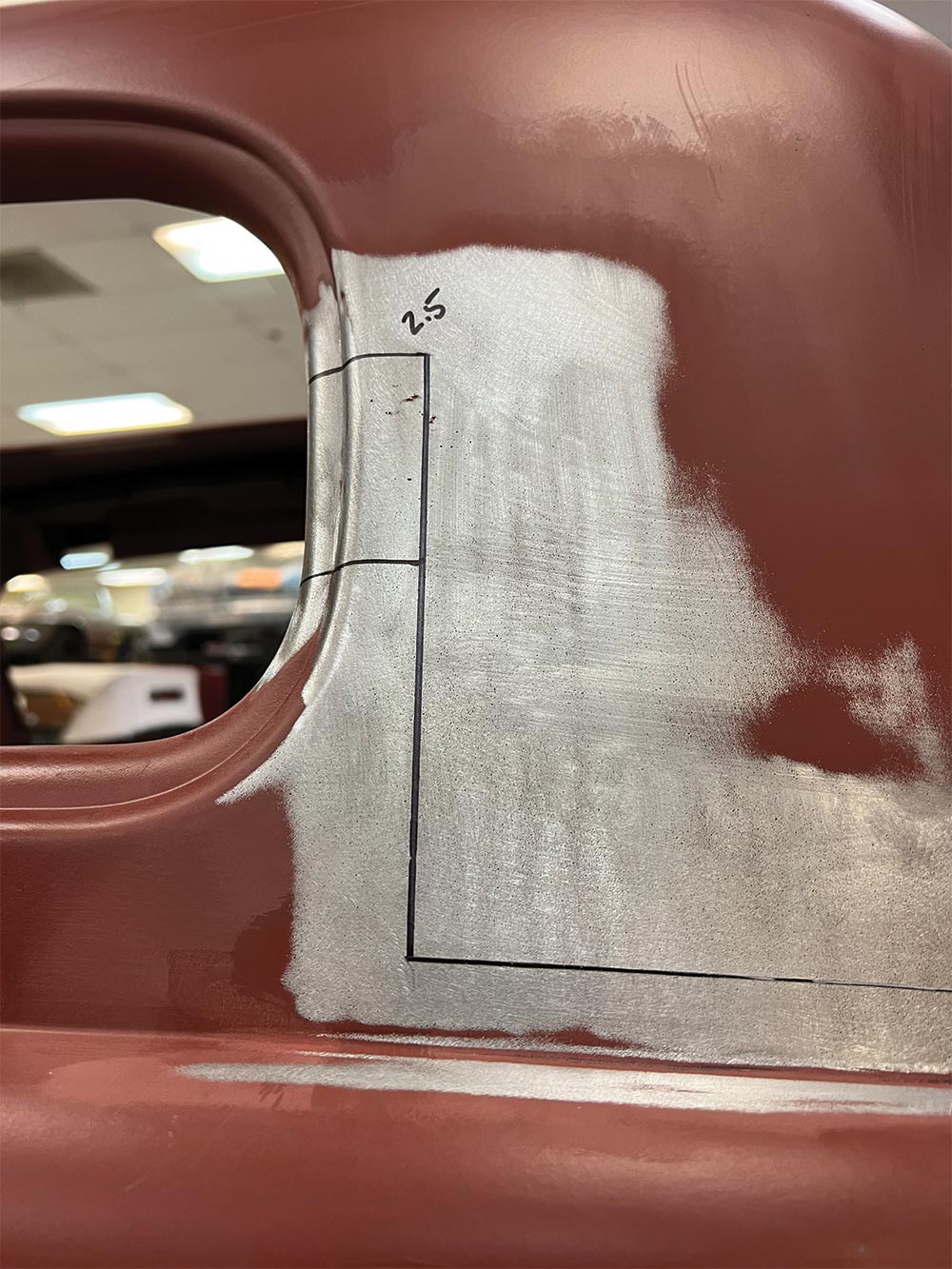

It wasn’t the chop itself that caught my attention—it’s a moderate cut (2-1/2 inches) on a somewhat common car. Rather, it was the way Nick Sinioris plotted his cut lines to minimize effort and maximize accuracy that stood out.

Welding—specifically the preparation for welding—really eats up time. Strong welds that don’t distort favor tight, consistent gaps. While nearly anyone can get such a gap along a short run, it takes a fair amount of skill and time to get that kind of gap over, say … a foot or 2. To get those tight, consistent gaps over that large area usually requires cutting a little wide of the scribe lines then creeping up on them with snips and files. And that kind of fit up usually requires making tabs to support the panels during the trimming process. The fit, trim, and repeat cycle takes a long time.

In oversimplified terms, Sinioris cut the top off, slid it down until the base overlapped the top, drilled through the overlapped area for temporary panel fasteners, then pinned everything together. That lets the lid fasten to the body without separate tabs or brackets.

Though neat, the ability for the top to serve as its own fixture is a secondary benefit to Sinioris’ method. The cut edge of the overlapping panel doubles as a guide for scribing and/or trimming the underlying panel. Cut right on that guide or cut through both panels simultaneously and you’ll get a panel gap that measures exactly the width of the cutting blade. Close up that gap for GTAW/TIG process as Sinioris did or leave it open for GMAW/MIG.

Because the top tapers toward its crown, the pillars misalign when chopped (the top emerges too short, lengthwise). One correction method extends the lid part of the top lengthwise to realign the posts. That maintains the windshield angle, which preserves the windshield’s seal.

The other method leans the windshield posts back. Doing that streamlines the windshield, which made it a popular technique in landspeed racing in the middle of the last century (see the Spalding brothers’ and SO-CAL Speed Shop’s coupes for examples). You’ll sometimes hear people refer to it as a Bonneville chop, and it’s how Sinioris chopped this top.

Along the way you’ll see a few other techniques that improve a chop’s integrity. For example, Sinioris uses a fixture to preserve hinge-pin alignment during reassembly, something that ensures that the doors will open and shut without binding. He also fabricated a lot of internal structural elements, like a tubular support that bridges the doorjambs and ties them into the top and inner fenderwells.

This is the first in a two-part series showing how Sinioris and the Hot Rods by Dean crew dropped a lid. Though some techniques are specific to Model 40 coupes, most of the process translates to other makes and models of the period, if only because they’re built largely the same way.

I still stand by my assertion that the world has enough top chopping stories. But as I’ve learned, for every rule there’s an exception. And so long as fabricators find those ways to improve the process and reduce the effort, we’re all eyes.

VOLUME 3 • ISSUE 27 • 2022